0708-1300/Class notes for Tuesday, September 11

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

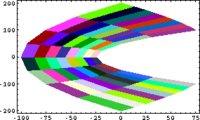

In Small Scales, Everything's Linear

|

[math]\displaystyle{ \longrightarrow }[/math] |

|

| [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \mapsto }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ z^2 }[/math] |

Code in Mathematica:

QuiltPlot[{f_,g_}, {x_, xmin_, xmax_, nx_}, {y_, ymin_, ymax_, ny_}] :=

Module[

{dx, dy, grid, ix, iy},

SeedRandom[1];

dx=(xmax-xmin)/nx;

dy=(ymax-ymin)/ny;

grid = Table[

{x -> xmin+ix*dx, y -> ymin+iy*dy},

{ix, 0, nx}, {iy, 0, ny}

];

grid = Map[({f, g} /. #)&, grid, {2}];

Show[

Graphics[Table[

{

RGBColor[Random[], Random[], Random[]],

Polygon[{

grid[[ix, iy]],

grid[[ix+1, iy]],

grid[[ix+1, iy+1]],

grid[[ix, iy+1]]

}]

},

{ix, nx}, {iy, ny}

]],

Frame -> True

]

]

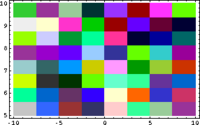

QuiltPlot[{x, y}, {x, -10, 10, 8}, {y, 5, 10, 8}]

QuiltPlot[{x^2-y^2, 2*x*y}, {x, -10, 10, 8}, {y, 5, 10, 8}]

See also 06-240/Linear Algebra - Why We Care.

Class Notes

Differentiability

Let [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] be two normed finite dimensional vector spaces and let [math]\displaystyle{ f:V\rightarrow W }[/math] be a function defined on a neighborhood of the point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]

Definition:

We say that [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is differentiable (diffable) if there is a linear map [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] so that

[math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{h\rightarrow0}\frac{|f(x+h)-f(x)-L(h)|}{|h|}. }[/math]

In this case we will say that [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] is a differential of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] and will denote it by [math]\displaystyle{ df_{x} }[/math].

Theorem

If [math]\displaystyle{ f:V\rightarrow W }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ g:U\rightarrow V }[/math] are diffable maps then the following asertions holds:

- [math]\displaystyle{ df_{x} }[/math] is unique.

- [math]\displaystyle{ d(f+g)_{x}=df_{x}+dg_{x} }[/math]

- If [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is linear then [math]\displaystyle{ df_{x}=f }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ d(f\circ g)_{x}=df_{g(x)}\circ dg_{x} }[/math]

- For every scalar number [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] it holds [math]\displaystyle{ d(\alpha f)_{x}=\alpha df_{x} }[/math]

Implicit Function Theorem

Example Although [math]\displaystyle{ x^2+y^2=1 }[/math] does not defines [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] as a function of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], in a neighborhood of [math]\displaystyle{ (0;-1) }[/math] we can define [math]\displaystyle{ g(x)=-\sqrt{1-x^2} }[/math] so that [math]\displaystyle{ x^2+g(x)^2=1 }[/math]. Furthermore, [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is differentiable with differential [math]\displaystyle{ dg_{x}=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}} }[/math]. This is a motivation for the following theorem.

Notation

If f:X\times Y\rightarrow Z then given x\in X we will define f_{[x]}:Y\rightarrow Z by f_{[x]}(y)=f(x;y)

Definition

[math]\displaystyle{ C^{p}(V) }[/math] will be the class of all functions defined on [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] with continuous partial derivatives up to order [math]\displaystyle{ p. }[/math]

Theorem(Implicit function theorem)

Let [math]\displaystyle{ f:\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m }[/math] be a [math]\displaystyle{ C^{1}(\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m) }[/math] function defined on a neighborhood [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] of the point [math]\displaystyle{ (x_0;y_0) }[/math] and such that [math]\displaystyle{ f(x_0;y_0)=0 }[/math] and suppose that [math]\displaystyle{ d(f_{[x]})_{y} }[/math] is non-singular then, the following results holds:

There is an open neighborhood of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ V\subset U }[/math], and a [math]\displaystyle{ diffable }[/math] function [math]\displaystyle{ g:V\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^m }[/math] such that for every [math]\displaystyle{ x\in V }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ f(x;g(x))=0. }[/math].