0708-1300/Class notes for Tuesday, October 16

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dror's Computer Program for C+[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] C

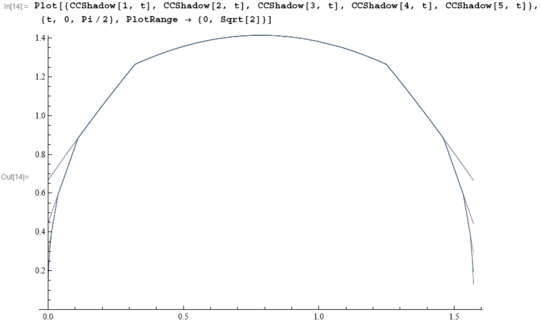

Our handout today is a printout of a Mathematica notebook that computes the measure of the projection of [math]\displaystyle{ C\times C }[/math] in a direction [math]\displaystyle{ t\in[0,\pi/2] }[/math] (where [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is the standard Cantor set). Here's the notebook, and here's a PDF version. Also, here's the main picture on that notebook:

Typed Class Notes - First Hour

Today's Agenda:

Proof of Sard's Theorem. That is, for [math]\displaystyle{ f:M^m\rightarrow N^n }[/math] being smooth, the measure [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math](critical values of f) = 0.

Comments regarding last class

1) In our counterexample to Sard's Theorem for the case of [math]\displaystyle{ C^1 }[/math] functions it was emphasized that there are functions f from a Cantor set C' to the Cantor set C. We then let [math]\displaystyle{ g(x,y) = f(x) + f(y) }[/math] and hence the critical values are [math]\displaystyle{ C+C = [0,2] }[/math] as was shown last time. The sketch of such an f was the same as last class.

Furthermore, in general we can find a [math]\displaystyle{ C^n }[/math] such function where we make the "bumps" in f smoother as needed and so [math]\displaystyle{ f(C') = C'' }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ C'' }[/math] is a "very thin" Cantor set. But now let [math]\displaystyle{ g(x,y,z,\ldots) = f(x) + f(y) + f(z) +\ldots }[/math] which will have an image of [math]\displaystyle{ C'' + C'' + C'' + \ldots = }[/math] an interval.

2) The code, and what the program does, for Dror's program (above) was described. It is impractical to describe it here in detail and so I will only comment that it computes the measure of [math]\displaystyle{ C+\alpha C }[/math] for various alpha and that the methodology relied on the 2nd method of proof regarding C+C done last class.

Proof of Sard's Theorem

Firstly, it is enough to argue locally.

Further, the technical assumption about manifolds that until now has been largely ignored is that our M must be second countable. Recall that this means that there is a countable basis for the topology on M.

As a counterexample to Sard's Theorem when M is NOT second countable consider the real line with the discrete topology, a zero dimensional manifold, mapping via the identity onto the real line with the normal topology. Every point in the real line is thus a critical point and the real line has non zero measure.

We can restrict our neighborhoods so that we can assume [math]\displaystyle{ M=\mathbb{R}^m }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ N=\mathbb{R}^n }[/math]

The general idea here is that if we consider a function g=f' that is nonzero at p but that f is zero at p, the inverse image is (in some chart) a straight line (a manifold). As such, we will inductively reduce the dimension from m down to zero. For m=0 there is nothing to prove. Hence we assume true for m-1.

Now, set [math]\displaystyle{ D_k = \{p | }[/math] all partial derivities of f of order [math]\displaystyle{ \leq k\} }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ k\geq 1 }[/math]

Set [math]\displaystyle{ D_0 = \{p\ |\ df_p }[/math] is not onto }. This is just the critical points.

Clearly [math]\displaystyle{ D_0\supset D_1\supset\ldots\supset D_i\supset\ldots\supset D_m }[/math]

We will show by backwards induction that [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(F(D_k)) = 0 }[/math]

Comment:

We have not actually defined the measure [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]. We use it merely to denote that [math]\displaystyle{ F(D_k)) }[/math] has measure zero, a concept that we DID define.

Claim 1

[math]\displaystyle{ F(D_m) }[/math] has measure 0.

Proof

W.L.O.G (without loss of generality) we can assume n=1. Intuitively this is reasonable as in lower dimensions the theorem is harder to prove; indeed, a set of size [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] in 1D becomes a smaller set of size [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon^2 }[/math] in 2D etc. More precisely, for [math]\displaystyle{ f = (f_1,\ldots,f_n) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ f(D_n)\subset f_1(D_m)\times{R}^{n-1} }[/math]. Applying the proposition that if A is of measure zero in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R} }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ A\times\mathbb{R}^{n-1} }[/math] is measure zero in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] we now see that assuming n=1 is justified.

Reminder

Taylor's Theorem: for smooth enough [math]\displaystyle{ g:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R} }[/math] and some [math]\displaystyle{ x_0 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) = \sum_{j=0}^{m} \frac{g^{(j)}(x_0)}{j!}(x-x_0)^j + \frac{g^{(m+1)}(t)}{(m+1)!}(x-x_0)^{m+1} }[/math] for some t between x and [math]\displaystyle{ x_0 }[/math].

For [math]\displaystyle{ x_0\in D_m }[/math] all but the last term vanishes and so we can conclude that f(x) is bounded by a constant times [math]\displaystyle{ (x-x_0)^{m+1} }[/math].

Now let us consider a box B in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^m }[/math] containing a section of [math]\displaystyle{ D_m }[/math]. We divide B into [math]\displaystyle{ C_1\lambda^m }[/math] boxes of side [math]\displaystyle{ 1/\lambda }[/math].

By Taylor's Theorem, [math]\displaystyle{ f(B_i)\subset }[/math] of an interval of length [math]\displaystyle{ C_2\frac{1}{\lambda^{m+1}} }[/math] where the constant [math]\displaystyle{ C_2 }[/math] is determined by Taylor's Theorem. Call this interval [math]\displaystyle{ I_i }[/math]

Hence,

[math]\displaystyle{ f(D_m)\subset\bigcup_{i:B_i\cap D_m \neq 0} f(B_i)\subset \bigcup_{i:B_i\cap D_m \neq 0}I_i }[/math]

But [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{i} length(I_i)\leq C_1\lambda^m C_2\frac{1}{\lambda^{m+1}} }[/math] which tends to zero as [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] tends to infinity.

Q.E.D for Claim 1

Claim 2

[math]\displaystyle{ f(D_k) }[/math] has measure zero for [math]\displaystyle{ k\geq 1 }[/math]. We just proved this for k=m.

Now, W.L.O.G. [math]\displaystyle{ D_{k+1} }[/math] is the empty set. If not, just consider [math]\displaystyle{ M^m - D_{k+1} }[/math] which is still a manifold as [math]\displaystyle{ D_{k+1} }[/math] is closed (as it is determined by the "closed" condition that a determinant equals zero)

So, there is some kth derivative g of f such that [math]\displaystyle{ dg\neq 0 }[/math].

So [math]\displaystyle{ D_k\subset g^{-1}(0) }[/math] but [math]\displaystyle{ g^{-1}(0) }[/math] is at least locally a manifold of dimension 1 less. So, [math]\displaystyle{ f(D_k)\subset f(D_k\cap g^{-1}(0) }[/math] which has measure zero due to our induction hypothesis.

Q.E.D for Claim 2

Claim 3

[math]\displaystyle{ f(D_0) }[/math] is of measure zero.

Recall [math]\displaystyle{ D_0 }[/math] is defined differently from the [math]\displaystyle{ D_k }[/math] and so requires a different technique to prove.

W.L.O.G. lets assume that [math]\displaystyle{ D_1 }[/math] is the empty set. So, some derivative of f is not zero. W.L.O.G. [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1} }[/math] is non zero near some point p. We can simply move to a coordinate system where this is true.

The idea here is to prove that the intersection with any "slice" has measure zero where we will then invoke a theorem that will claim everything has measure zero.

So, let U be an open neighborhood of a point [math]\displaystyle{ p\in M }[/math]. Consider [math]\displaystyle{ f_1:U\rightarrow\mathbb{R} }[/math] and let [math]\displaystyle{ df_1 }[/math] be onto. Using our previous theorem for the local structure of such a submersion W.L.O.G. let us assume [math]\displaystyle{ f_1:\mathbb{R}^m\rightarrow\mathbb{R} }[/math] via [math]\displaystyle{ (x_1,\ldots,x_m)\mapsto x_1 }[/math]. That is, [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 = x_1 }[/math].

Our differential df then is just the matrix whose first row consists of [math]\displaystyle{ (1,0,\ldots,0) }[/math]. Then df is onto if the submatrix consisting of all but the first row and first column is invertible.

For notational convenience let us say [math]\displaystyle{ f =(f_1,f_{rest}) }[/math].

Now define [math]\displaystyle{ U_t = \{t\times\mathbb{R}^{m-1}\} }[/math] Also lets denote "critical points of f by CP(f) and "critical values of f" by CV(f)

Claim 4

The [math]\displaystyle{ CP(f) = \bigcup_{t\in\mathbb{R}}\{t\}\times CP(f_{rest}|_{U_t}) }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \Rightarrow }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ CV(f) = \bigcup_{t\in\mathbb{R}}\{t\}\times CV(f_{rest}|_{U_t}) }[/math].

But [math]\displaystyle{ CV(f_{rest}|_{U_t}) }[/math] has measure zero by our induction.

Lemma 1

If [math]\displaystyle{ A\subset I^2 }[/math] is closed and has [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(A\cap(\{t\}\times I)) = 0\ \forall t }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \mu(A)=0 }[/math].

Proof

Note: We prove this significantly differently then in Bredon

Sublemma

If [math]\displaystyle{ \{t\}\times U }[/math] for an open U cover [math]\displaystyle{ \{t\}\times I\cap A }[/math] for a closed A then [math]\displaystyle{ \exists\epsilon\gt 0 }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ (t-\epsilon,t+\epsilon)\times U\supset (t-\epsilon,t+\epsilon)\times I\cap A }[/math]

Indeed, let [math]\displaystyle{ d:A-(I\times U)\rightarrow\mathbb{R} }[/math] be [math]\displaystyle{ d(x) = |x_1-t| }[/math] then d is a continuous function of a compact set and so obtains a minimum and since d>0 then [math]\displaystyle{ min(d)\gt 0 \rightarrow d\gt \epsilon\gt 0 }[/math]. But this [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] works for the claim. Q.E.D

The rest of the proof of Lemma 1, and of Sard's Theorem will be left until next class