0708-1300/Class notes for Tuesday, February 5: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{0708-1300/Navigation}} |

{{0708-1300/Navigation}} |

||

{{In Preparation}} |

|||

==Unbased Covering Spaces== |

==Unbased Covering Spaces== |

||

| Line 77: | Line 76: | ||

==A Deep Thought Question== |

==A Deep Thought Question== |

||

What does it at all mean "<math>{\mathcal G}\circ{\mathcal F}</math> is equivalent to the identity functor" (and first, why can't it simply ''be'' the identity functor)? And even harder, what does it at all mean for two categories to be "equivalent"? If you answer this question correctly, you'll probably re-invent the notions of "natural transformation between two functors" and "natural equivalence", that gave the historical impetus for the development of category theory. |

What does it at all mean "<math>{\mathcal G}\circ{\mathcal F}</math> is equivalent to the identity functor" (and first, why can't it simply ''be'' the identity functor)? And even harder, what does it at all mean for two categories to be "equivalent"? If you answer this question correctly, you'll probably re-invent the notions of "natural transformation between two functors" and "natural equivalence", that gave the historical impetus for the development of category theory. |

||

From the Wikipedia entry for [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_transformation Natural Transformation]: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

Saunders Mac Lane, one of the founders of category theory, is said to have remarked, "I didn't invent categories to study functors; I invented them to study natural transformations." Just as the study of groups is not complete without a study of homomorphisms, so the study of categories is not complete without the study of functors. The reason for Mac Lane's comment is that the study of functors is itself not complete without the study of natural transformations. |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

The context of Mac Lane's remark was the axiomatic theory of homology. Different ways of constructing homology could be shown to coincide: for example in the case of a simplicial complex the groups defined directly, and those of the singular theory, would be isomorphic. What cannot easily be expressed without the language of natural transformations is how homology groups are compatible with morphisms between objects, and how two equivalent homology theories not only have the same homology groups, but also the same morphisms between those groups. |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

Revision as of 18:43, 4 February 2008

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unbased Covering Spaces

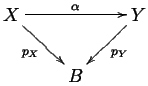

Let [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] be a topological space and let [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal C}(B) }[/math] be the category of covering spaces of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]: The category whose objects are (unbased!) coverings [math]\displaystyle{ X\to B }[/math] and whose morphisms are maps between such coverings that commute with the covering projections - a morphism between [math]\displaystyle{ p_X:X\to B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p_Y:Y\to B }[/math] is a map [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha:X\to Y }[/math] so that the diagram below is commutative:

|

Every topologists' highest hope is to find that her/his favourite category of topological objects is equivalent to some category of easily understood algebraic objects. The following theorem realizes this dream in full in the case of the category [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal C}(B) }[/math] of covering spaces of any reasonable base space [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]:

Theorem 1. (Classification of covering spaces)

- If [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is connected and locally connected with base point [math]\displaystyle{ b_0 }[/math] and fundamental group [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B,b_0) }[/math], then the map which assigns to every covering [math]\displaystyle{ p:X\to B }[/math] its fiber [math]\displaystyle{ p^{-1}(b_0) }[/math] over the basepoint [math]\displaystyle{ b_0 }[/math] induces a functor [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F} }[/math] from the category [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal C}(B) }[/math] of coverings of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] to the category [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal S}(G) }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-sets - sets with a right [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-action and set maps that respect the [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] action.

- If in addition [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is semi-locally simply connected then the functor [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F} }[/math] is an equivalence of categories. (In fact, this is iff).

If indeed the categories [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal C}(B) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal S}(G) }[/math] are equivalent, one should be able to extract everything topological about a covering [math]\displaystyle{ p:X\to B }[/math] from its associated [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-set [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F}(X)=p^{-1}(b_0) }[/math]. The following theorem shows this to be right in at least two ways:

Theorem 2.

- The set of connected components of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is in a bijective correspondence with the set of orbits of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F}(X) }[/math].

- Let [math]\displaystyle{ x_0\in{\mathcal F}(X)=p^{-1}(b_0) }[/math] be a basepoint for [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] that covers the basepoint [math]\displaystyle{ b_0 }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]. Then the fundamental group [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_1(X,x_0) }[/math] is isomorphic via the projection [math]\displaystyle{ p_\star }[/math] into [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B,b_0) }[/math] to the stabilizer group [math]\displaystyle{ \{h\in G: xh=x\} }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ x_0\in{\mathcal F}(X) }[/math].

(Both assertions of this theorem can be sharpened to deal with morphisms as well, but we will not bother to do so).

Based Covering Spaces

There are similar theorems (call them theorem 1' and theorem 2') relating the category of based covering spaces with the category of based [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-sets.

The Main Point

Ok. Every math technician can spend some time and effort and understand the statements and (only then) the proofs of these two theorems. Your true challenge is to digest the following statement:

| All there is to know about covering spaces follows from these two theorems |

In particular, the following facts are all simple algebraic corollaries of these theorems:

Corollary 1. If [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is connected then its covering number (="number of decks") is equal to the index of [math]\displaystyle{ H=p_\star\pi_1(X) }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B) }[/math], and the decks of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] are in a non-canonical correspondence with the left cosets [math]\displaystyle{ H\backslash G }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math].

Corollary 2. If [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is semi-locally simply connected, there exists a unique (up to base-point-preserving isomorphism) "universal covering space [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]" (a connected and simply connected covering [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math]).

Corollary 3. The group of automorphisms of the universal covering [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] is equal to [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B) }[/math].

Corollary 4. [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_1(S^1)={\mathbb Z} }[/math].

Corollary 5. [math]\displaystyle{ \pi_1(SO(3))={\mathbb Z}/2{\mathbb Z} }[/math].

Corollary 6. If [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is semi-locally simply connected, then for every [math]\displaystyle{ H\lt G=\pi_1(B) }[/math] there is a unique (up to base-point-preserving isomorphism) connected covering space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ p_\star\pi_1(X)=H }[/math].

Corollary 7. If [math]\displaystyle{ X_i }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ i=1,2 }[/math] are connected coverings of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] with groups [math]\displaystyle{ H_i=p_{i\star}\pi_1(X_i) }[/math] and if [math]\displaystyle{ H_1\lt H_2 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] is a covering of [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math] of covering number [math]\displaystyle{ (H_2:H_1) }[/math].

Corollary 8. If [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is semi-locally simply connected there is a bijection between conjugacy classes of subgroups of [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B) }[/math] and unbased connected coverings of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

Corollary 9. A connected covering [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is normal (for any [math]\displaystyle{ x_1,x_2\in p^{-1}(b) }[/math] theres an automorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \tau x_1=x_2 }[/math]) iff its group [math]\displaystyle{ p_\star\pi_1(X) }[/math] is normal in [math]\displaystyle{ G=\pi_1(B) }[/math].

Corollary 10. If [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a connected covering of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ H=p_\star\pi_1(X) }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Aut}(X)=N_G(H)/H }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ N_G(H) }[/math] is the normalizer of [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math].

Proposition 11. If we forgot anything, it follows too.

Steps in the proofs of Theorem 1 and 2

- Use path liftings to construct a right action of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ p^{-1}(b_0) }[/math].

- Show that this is indeed a group action and that morphisms of coverings induce morphisms of right [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-sets.

- Start the construction of an "inverse" functor [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G} }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F} }[/math]: Use spelunking (cave exploration) to construct a universal covering [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math], if [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is semi-locally simply connected.

- Show that [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F}(U)=G }[/math].

- Use the construction of [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] or the general lifting property for covering spaces to show that there is a left action of [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math].

- For a general right [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-set [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math] set [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G}(S)=S\times_GU=\{(s,u)\in S\times U\}/(sg,u)\sim(s,gu) }[/math] and show that [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G}(S) }[/math] is a covering of [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal F}({\mathcal G}(S))=S }[/math].

- Show that [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G} }[/math] is compatible with maps between right [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]-sets.

- Understand the relationship between connected components and orbits.

- Prove Theorem 2.

- Use the existence and uniqueness of lifts to show that [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G}\circ{\mathcal F} }[/math] is equivalent to the identity functor (working connected component by connected component).

A Deep Thought Question

What does it at all mean "[math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal G}\circ{\mathcal F} }[/math] is equivalent to the identity functor" (and first, why can't it simply be the identity functor)? And even harder, what does it at all mean for two categories to be "equivalent"? If you answer this question correctly, you'll probably re-invent the notions of "natural transformation between two functors" and "natural equivalence", that gave the historical impetus for the development of category theory.

From the Wikipedia entry for Natural Transformation:

Saunders Mac Lane, one of the founders of category theory, is said to have remarked, "I didn't invent categories to study functors; I invented them to study natural transformations." Just as the study of groups is not complete without a study of homomorphisms, so the study of categories is not complete without the study of functors. The reason for Mac Lane's comment is that the study of functors is itself not complete without the study of natural transformations.

The context of Mac Lane's remark was the axiomatic theory of homology. Different ways of constructing homology could be shown to coincide: for example in the case of a simplicial complex the groups defined directly, and those of the singular theory, would be isomorphic. What cannot easily be expressed without the language of natural transformations is how homology groups are compatible with morphisms between objects, and how two equivalent homology theories not only have the same homology groups, but also the same morphisms between those groups.