0708-1300/Class notes for Thursday, September 20: Difference between revisions

| (14 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

Come to {{Home Link|Talks/Fields-0709/|my talk}} today at 4:30PM at the Fields Institute! |

Come to {{Home Link|Talks/Fields-0709/|my talk}} today at 4:30PM at the Fields Institute! |

||

{{0708-1300/Class Notes}} |

|||

PDF file of the class notes typed up in latex can be located [http://individual.utoronto.ca/tbazett/mat1300/0708-1300-Class_Notes_latex_20-09.pdf here] |

PDF file of the class notes typed up in latex can be located [http://individual.utoronto.ca/tbazett/mat1300/0708-1300-Class_Notes_latex_20-09.pdf here] |

||

Tex version of the file is also avaliable [http://individual.utoronto.ca/tbazett/mat1300/0708-1300-Class_Notes_latex_20-09.tex here] so that people can easily make changes and repost here if they wish. |

Tex version of the file is also avaliable [http://individual.utoronto.ca/tbazett/mat1300/0708-1300-Class_Notes_latex_20-09.tex here] so that people can easily make changes and repost here if they wish. |

||

==Exercise== |

|||

{{0708-1300/Solution Warning}} |

|||

Configurations of a Generalized Cockroach (not entirely rigourous) |

|||

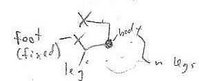

Let <math>C_n</math> be the manifold of configurations of a "cockroach" with <math>n</math> legs: |

|||

[[Image:0708-1300-cockroach-labelling.jpg||center|200px|]] |

|||

Q: What is <math>C_n</math>? |

|||

In particular, what is <math>C_6</math>? |

|||

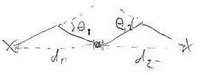

<math>n=2</math>: Consider <math>C_2</math>. |

|||

[[Image:0708-1300-cockroach-C2.jpg||left||200px]] |

|||

As in the picture, label the angles of the joints <math>\theta_1</math> and <math>\theta_2</math> and the distances from the body to the feet <math>d_1</math> and <math>d_2</math> respectively. |

|||

The value of <math>\theta_i</math> determines the value of <math>d_i</math>. |

|||

So, given values <math>(\theta_1, \theta_2)</math>, possible configurations are given by positions of the body, which must have distance <math>d_i</math> from the <math>i</math>th foot. |

|||

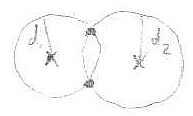

That is, the body must lie on the intersection of the two circles of radius <math>d_i</math> centred at the <math>i</math>th foot: |

|||

[[Image:0708-1300-cockroach-twocircles.jpg||center||]] |

|||

There are <math>0, 1, </math> or <math>2</math> solutions for the body position. |

|||

If we look only at the top body position, the pair <math>(\theta_1, \theta_2)</math> determines a unique configuration. |

|||

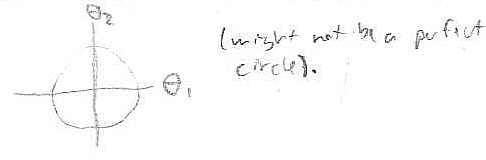

So, we can plot the subset on <math>\R^2_{(\theta_1,\theta_2)}</math>: |

|||

[[Image:0708-1300-cockroach-C2region.jpg||center||]] |

|||

The boundary points are where the "top" solution is in fact the unique solution. |

|||

By symmetry, taking the bottom solution gives us a similar region, and since the boundaries are where the top and bottom solutions coincide (there is only one solution along the boundary), the entire manifold is given by gluing the boundaries together. |

|||

This gives a sphere. |

|||

<math>n=3</math>: Configurations with <math>3</math> legs consist of a configuration with <math>2</math> legs plus the configuration of the third leg. |

|||

The configuration of the first <math>2</math> legs fixes the position of the body - and thus, the distance <math>d_3</math> from the third foot to the body. |

|||

For certain configurations of the first two legs, the body is too far from the third foot, so these are not found as part of configurations with three feet. |

|||

When the distance from the body to the third foot equals the length of the third leg completely extended, this gives a unique configuration of the <math>3</math>-legged cockroach. |

|||

Any closer and there are two possible configurations, corresponding to the two ways that the third joint can bend. |

|||

Let <math>R</math> be the region in <math>C_2 = S_2</math> where the distance to the third leg is close enough to give solutions. |

|||

The boundary of <math>R</math> is a curve, consisting of all the points at which there is a unique solution: |

|||

[[Image:0708-1300-cockroach-regionR.jpg||center||]] |

|||

So the manifold <math>C_3</math> is given by taking two copies of <math>R</math> and gluing their boundaries together. |

|||

This gives a sphere. |

|||

<math>n \geq 3</math>: Likewise, given that <math>C_n = S_2</math>, it follows that <math>C_{n+1} = S_2</math> also. |

|||

In particular, <math>C_6 = S_2</math>. |

|||

===Dror's Evaluation=== |

|||

The solution for <math>n=2</math> seems right but hard to understand. For <math>n=3</math> the solution is absolutely right. Unfortunately for <math>n>3</math> the solution is wrong. (Why?) |

|||

--[[User:Drorbn|Drorbn]] 19:46, 24 September 2007 (EDT) |

|||

===A combinatorial solution to the roach problem=== |

|||

The answer: |

|||

An n-legged roach has configuration space = a torus with <math>1+2^{n-3}(n-4)</math> holes! |

|||

The reason: |

|||

The configuration space of a roach can be represented as a graph as follows. Each face is the domain the body moves in when we fix which way each leg is bent. Since each of the n legs can be bent in 2 directions, we have <math>2^n</math> faces. Each edge is the boundary where one leg is straight (it borders the face where the leg is bent in the other direction). The vertices therefore correspond to positions where two adjacent legs are straight. This means that each vertex has degree four. (for those of you unfamiliar with graph theory lingo, degree 4 means that we have 4 edges from each vertex. In this case we have also four faces) We can now calculate the number of edges, vertices and faces (E, V, F) of an n-legged roach: |

|||

F = <math>2^n</math> |

|||

E = <math>nF/2</math> = <math>2^{n-1}n</math> |

|||

V = <math>2E/degree</math> = <math>2^{n-2}n</math> |

|||

(the above calculation of E in terms of F and V in terms of E is a fun counting argument, if you can’t figure it out ask me) |

|||

Now we compute the Euler genus which tells us what kind of surface this graph is: |

|||

Euler genus = <math>2 - V + E - F = 2 + 2^{n-2}(n-4)</math> |

|||

Since a k-holed torus has genus 2k (the sphere has genus 0), the configuration space of an n-legged roach is a |

|||

k = <math>1 + 2^{n-3}(n-4)</math> -holed torus. |

|||

===a non combinatorial, cut-and-paste topology solution=== |

|||

which, conveniently, gives the same answer as my combinatorial solution above. |

|||

{| align=center |

|||

|- align=center |

|||

|[[Image:0708-1300roach1.jpg|200px]] |

|||

|[[Image:0708-1300roach2001.jpg|200px]] |

|||

|} |

|||

please e-mail me if you have questions, comments or a burning desire for more rigour. |

|||

a webpage to go to if you want info about how to turn my recursive formula for Cn into my non-recursive one is: |

|||

http://web.cs.wpi.edu/~cs504/s99/notes/recurrence/solve/solve.html |

|||

--[[User:Katiemann|Katiemann]] 10:42, 5 November 2007 (EST) |

|||

==Enrichment: Configuration Spaces of Mechanical Systems== |

|||

As Prof. Bar-Natan mentioned in class, manifolds are quite useful for studying the physics of mechanical systems like robots and steam engines. There is actually a very general mathematical theory of rigid body mechanics that makes plenty of use of differential geometry. See, for example, |

|||

{{ref|BulloLewis_04}} for a discussion of one of these models and its application to nonlinear control theory for mechanical systems. The following is a brief introduction to the idea of a mechanical system's <i>configuration space</i>, and makes use of the notation of {{ref|BulloLewis_04}}. |

|||

Imagine that you have some rigid body <math>B\!</math> floating around in space. The first thing to do is to set up an orthonormal frame <math>(O_{spatial},(s_1,s_2,s_3))\!</math> with respect to which we will describe <math>B\!</math>'s position. Here <math>O_{spatial}\!</math> is some point in Euclidean (affine) space which serves as the origin of our coordinate system and <math>(s_1,s_2,s_3)\!</math> is an orthonormal basis for Euclidean space centred at <math>O_{spatial}\!</math>. |

|||

Now suppose that we rigidly attach a frame <math>(O_{body},(b_1,b_2,b_3))\!</math> to <math>B\!</math> in the sense that the frame's origin is fixed to a specific point on the body (such as the centre of mass) and the basis <math>(b_1,b_2,b_3)\!</math> rotates around with <math>B\!</math>. We can now specify <math>B\!</math>'s configuration with the vector |

|||

::<math>r = O_{body} - O_{spatial} \in \mathbb{R}^3\!</math> |

|||

and the matrix <math> R \in SO(3;\mathbb{R})\!</math> which gives the orientation of the basis <math>(b_1,b_2,b_3)\!</math> relative to <math>(s_1,s_2,s_3)\!</math>. Here <math>SO(3;\mathbb{R})\!</math> is the group of <math>3\times 3\!</math> real matrices with unit determinant---the group of rotations of <math>\mathbb{R}^3\!</math>. Concisely, the configuration space of a rigid body is the space <math>Q_{free}=SO(3;\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^3\!</math>. |

|||

Lucky for us, <math>SO(3;\mathbb{R})\!</math> is actually a manifold. It's an example of something called a <i>Lie group</i>, which is a group that is also a manifold and whose group operations are smooth according to the differentiable structure of the manifold. Hence <math>Q_{free}\!</math> is also a manifold. |

|||

Now imagine we have <math>k\!</math> rigid bodies. If the bodies are free to move around independently, and if we briefly suspend disbelief and allow them to pass right through each other instead of colliding, our configuration space is <math>Q_{free}^k= \left(SO(3;\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^3\right)^k</math>. If, on the other hand, the bodies are interconnected---ie., their motions are not independent---or if the motion of the bodies is constrained in some other way, then the configuration space for the system will be some subset <math>Q \subset Q_{free}^k\!</math>. In fact, it is (usually) a <i>submanifold</i>. |

|||

This situation is precisely what's happening with the roach's configuration. In this case the system consists of 12 rigid bodies (six legs composed of two segments each) that are constrained to move in a plane, connected together at their ends, and pinned down. |

|||

Hopefully, it is starting to become clear how we can model some of the physics now: we can describe the motion of a mechanical system with a curve <math>\gamma : I \rightarrow Q\!</math> where <math>I \subset \mathbb{R}\!</math> is an interval. The velocities of all the bodies (both translational and rotational) at time <math>t\!</math>are encapsulated in the tangent vector <math>\gamma'(t) \in T_{\gamma(t)}Q\!</math>. Similarly, there are nice differential-geometric ways of describing the kinetic and potential energies, forces and so on. |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{note|BulloLewis_04}}Francesco Bullo and Andrew D. Lewis, <i>Geometric Control of Mechanical Systems: Modeling, Analysis, and Design for Simple Mechanical Control Systems</i>, Springer-Verlag, New York-Heidelberg-Berlin, 2004. Number 49 in <i>Texts in Applied Mathematics.</i> |

|||

Latest revision as of 07:43, 15 November 2007

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dror's Note

Come to my talk today at 4:30PM at the Fields Institute!

Class Notes

The notes below are by the students and for the students. Hopefully they are useful, but they come with no guarantee of any kind.

PDF file of the class notes typed up in latex can be located here

Tex version of the file is also avaliable here so that people can easily make changes and repost here if they wish.

Exercise

The solution(s) below are by the students and for the students. Hopefully they are useful, but they come with no guarantee of any kind.

Configurations of a Generalized Cockroach (not entirely rigourous)

Let [math]\displaystyle{ C_n }[/math] be the manifold of configurations of a "cockroach" with [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] legs:

Q: What is [math]\displaystyle{ C_n }[/math]? In particular, what is [math]\displaystyle{ C_6 }[/math]?

[math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math]: Consider [math]\displaystyle{ C_2 }[/math].

As in the picture, label the angles of the joints [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_2 }[/math] and the distances from the body to the feet [math]\displaystyle{ d_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ d_2 }[/math] respectively.

The value of [math]\displaystyle{ \theta_i }[/math] determines the value of [math]\displaystyle{ d_i }[/math]. So, given values [math]\displaystyle{ (\theta_1, \theta_2) }[/math], possible configurations are given by positions of the body, which must have distance [math]\displaystyle{ d_i }[/math] from the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]th foot.

That is, the body must lie on the intersection of the two circles of radius [math]\displaystyle{ d_i }[/math] centred at the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]th foot:

There are [math]\displaystyle{ 0, 1, }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] solutions for the body position.

If we look only at the top body position, the pair [math]\displaystyle{ (\theta_1, \theta_2) }[/math] determines a unique configuration.

So, we can plot the subset on [math]\displaystyle{ \R^2_{(\theta_1,\theta_2)} }[/math]:

The boundary points are where the "top" solution is in fact the unique solution.

By symmetry, taking the bottom solution gives us a similar region, and since the boundaries are where the top and bottom solutions coincide (there is only one solution along the boundary), the entire manifold is given by gluing the boundaries together. This gives a sphere.

[math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math]: Configurations with [math]\displaystyle{ 3 }[/math] legs consist of a configuration with [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] legs plus the configuration of the third leg. The configuration of the first [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] legs fixes the position of the body - and thus, the distance [math]\displaystyle{ d_3 }[/math] from the third foot to the body.

For certain configurations of the first two legs, the body is too far from the third foot, so these are not found as part of configurations with three feet. When the distance from the body to the third foot equals the length of the third leg completely extended, this gives a unique configuration of the [math]\displaystyle{ 3 }[/math]-legged cockroach. Any closer and there are two possible configurations, corresponding to the two ways that the third joint can bend.

Let [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] be the region in [math]\displaystyle{ C_2 = S_2 }[/math] where the distance to the third leg is close enough to give solutions. The boundary of [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is a curve, consisting of all the points at which there is a unique solution:

So the manifold [math]\displaystyle{ C_3 }[/math] is given by taking two copies of [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] and gluing their boundaries together. This gives a sphere.

[math]\displaystyle{ n \geq 3 }[/math]: Likewise, given that [math]\displaystyle{ C_n = S_2 }[/math], it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ C_{n+1} = S_2 }[/math] also. In particular, [math]\displaystyle{ C_6 = S_2 }[/math].

Dror's Evaluation

The solution for [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math] seems right but hard to understand. For [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math] the solution is absolutely right. Unfortunately for [math]\displaystyle{ n\gt 3 }[/math] the solution is wrong. (Why?)

--Drorbn 19:46, 24 September 2007 (EDT)

A combinatorial solution to the roach problem

The answer: An n-legged roach has configuration space = a torus with [math]\displaystyle{ 1+2^{n-3}(n-4) }[/math] holes!

The reason: The configuration space of a roach can be represented as a graph as follows. Each face is the domain the body moves in when we fix which way each leg is bent. Since each of the n legs can be bent in 2 directions, we have [math]\displaystyle{ 2^n }[/math] faces. Each edge is the boundary where one leg is straight (it borders the face where the leg is bent in the other direction). The vertices therefore correspond to positions where two adjacent legs are straight. This means that each vertex has degree four. (for those of you unfamiliar with graph theory lingo, degree 4 means that we have 4 edges from each vertex. In this case we have also four faces) We can now calculate the number of edges, vertices and faces (E, V, F) of an n-legged roach:

F = [math]\displaystyle{ 2^n }[/math]

E = [math]\displaystyle{ nF/2 }[/math] = [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{n-1}n }[/math]

V = [math]\displaystyle{ 2E/degree }[/math] = [math]\displaystyle{ 2^{n-2}n }[/math]

(the above calculation of E in terms of F and V in terms of E is a fun counting argument, if you can’t figure it out ask me) Now we compute the Euler genus which tells us what kind of surface this graph is: Euler genus = [math]\displaystyle{ 2 - V + E - F = 2 + 2^{n-2}(n-4) }[/math] Since a k-holed torus has genus 2k (the sphere has genus 0), the configuration space of an n-legged roach is a k = [math]\displaystyle{ 1 + 2^{n-3}(n-4) }[/math] -holed torus.

a non combinatorial, cut-and-paste topology solution

which, conveniently, gives the same answer as my combinatorial solution above.

|

|

please e-mail me if you have questions, comments or a burning desire for more rigour.

a webpage to go to if you want info about how to turn my recursive formula for Cn into my non-recursive one is: http://web.cs.wpi.edu/~cs504/s99/notes/recurrence/solve/solve.html

--Katiemann 10:42, 5 November 2007 (EST)

Enrichment: Configuration Spaces of Mechanical Systems

As Prof. Bar-Natan mentioned in class, manifolds are quite useful for studying the physics of mechanical systems like robots and steam engines. There is actually a very general mathematical theory of rigid body mechanics that makes plenty of use of differential geometry. See, for example, [BulloLewis_04] for a discussion of one of these models and its application to nonlinear control theory for mechanical systems. The following is a brief introduction to the idea of a mechanical system's configuration space, and makes use of the notation of [BulloLewis_04].

Imagine that you have some rigid body [math]\displaystyle{ B\! }[/math] floating around in space. The first thing to do is to set up an orthonormal frame [math]\displaystyle{ (O_{spatial},(s_1,s_2,s_3))\! }[/math] with respect to which we will describe [math]\displaystyle{ B\! }[/math]'s position. Here [math]\displaystyle{ O_{spatial}\! }[/math] is some point in Euclidean (affine) space which serves as the origin of our coordinate system and [math]\displaystyle{ (s_1,s_2,s_3)\! }[/math] is an orthonormal basis for Euclidean space centred at [math]\displaystyle{ O_{spatial}\! }[/math].

Now suppose that we rigidly attach a frame [math]\displaystyle{ (O_{body},(b_1,b_2,b_3))\! }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ B\! }[/math] in the sense that the frame's origin is fixed to a specific point on the body (such as the centre of mass) and the basis [math]\displaystyle{ (b_1,b_2,b_3)\! }[/math] rotates around with [math]\displaystyle{ B\! }[/math]. We can now specify [math]\displaystyle{ B\! }[/math]'s configuration with the vector

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = O_{body} - O_{spatial} \in \mathbb{R}^3\! }[/math]

and the matrix [math]\displaystyle{ R \in SO(3;\mathbb{R})\! }[/math] which gives the orientation of the basis [math]\displaystyle{ (b_1,b_2,b_3)\! }[/math] relative to [math]\displaystyle{ (s_1,s_2,s_3)\! }[/math]. Here [math]\displaystyle{ SO(3;\mathbb{R})\! }[/math] is the group of [math]\displaystyle{ 3\times 3\! }[/math] real matrices with unit determinant---the group of rotations of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^3\! }[/math]. Concisely, the configuration space of a rigid body is the space [math]\displaystyle{ Q_{free}=SO(3;\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^3\! }[/math].

Lucky for us, [math]\displaystyle{ SO(3;\mathbb{R})\! }[/math] is actually a manifold. It's an example of something called a Lie group, which is a group that is also a manifold and whose group operations are smooth according to the differentiable structure of the manifold. Hence [math]\displaystyle{ Q_{free}\! }[/math] is also a manifold.

Now imagine we have [math]\displaystyle{ k\! }[/math] rigid bodies. If the bodies are free to move around independently, and if we briefly suspend disbelief and allow them to pass right through each other instead of colliding, our configuration space is [math]\displaystyle{ Q_{free}^k= \left(SO(3;\mathbb{R}) \times \mathbb{R}^3\right)^k }[/math]. If, on the other hand, the bodies are interconnected---ie., their motions are not independent---or if the motion of the bodies is constrained in some other way, then the configuration space for the system will be some subset [math]\displaystyle{ Q \subset Q_{free}^k\! }[/math]. In fact, it is (usually) a submanifold.

This situation is precisely what's happening with the roach's configuration. In this case the system consists of 12 rigid bodies (six legs composed of two segments each) that are constrained to move in a plane, connected together at their ends, and pinned down.

Hopefully, it is starting to become clear how we can model some of the physics now: we can describe the motion of a mechanical system with a curve [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma : I \rightarrow Q\! }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ I \subset \mathbb{R}\! }[/math] is an interval. The velocities of all the bodies (both translational and rotational) at time [math]\displaystyle{ t\! }[/math]are encapsulated in the tangent vector [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma'(t) \in T_{\gamma(t)}Q\! }[/math]. Similarly, there are nice differential-geometric ways of describing the kinetic and potential energies, forces and so on.

References

[BulloLewis_04] ^ Francesco Bullo and Andrew D. Lewis, Geometric Control of Mechanical Systems: Modeling, Analysis, and Design for Simple Mechanical Control Systems, Springer-Verlag, New York-Heidelberg-Berlin, 2004. Number 49 in Texts in Applied Mathematics.