0708-1300/Class notes for Tuesday, September 11: Difference between revisions

| (7 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

See also [[06-240/Linear Algebra - Why We Care]]. |

See also [[06-240/Linear Algebra - Why We Care]]. |

||

{{0708-1300/Class Notes}} |

|||

===Differentiability=== |

===Differentiability=== |

||

Let <math>U</math>, <math>V</math> and <math>W</math> be two normed finite dimensional vector spaces and let <math>f:V\rightarrow W</math> be a function defined on a neighborhood of the point <math>x</math> |

Let <math>U</math>, <math>V</math> and <math>W</math> be two normed finite dimensional vector spaces and let <math>f:V\rightarrow W</math> be a function defined on a neighborhood of the point <math>x</math>. |

||

'''Definition:''' |

'''Definition:''' |

||

We say that <math>f</math> is differentiable (''diffable'') if there is a linear map <math>L</math> so that |

We say that <math>f</math> is differentiable (''diffable'') at <math>x</math> if there is a linear map <math>L</math> so that |

||

<math>\lim_{h\rightarrow0}\frac{|f(x+h)-f(x)-L(h)|}{|h|}.</math> |

<math>\lim_{h\rightarrow0}\frac{|f(x+h)-f(x)-L(h)|}{|h|}=0.</math> |

||

In this case we will say that <math>L</math> is a differential of <math>f</math> and will denote it by <math>df_{x}</math>. |

In this case we will say that <math>L</math> is a differential of <math>f</math> at <math>x</math> and will denote it by <math>df_{x}</math>. |

||

'''Theorem''' |

'''Theorem''' |

||

If <math>f:V\rightarrow W</math> and <math>g:U\rightarrow V</math> are ''diffable'' maps then the following |

If <math>f:V\rightarrow W</math> and <math>g:U\rightarrow V</math> are ''diffable'' maps then the following assertions hold: |

||

# <math>df_{x}</math> is unique. |

# <math>df_{x}</math> is unique. |

||

# <math>d(f+g)_{x}=df_{x}+dg_{x}</math> |

# <math>d(f+g)_{x}=df_{x}+dg_{x}</math> |

||

# If <math>f</math> is linear then <math>df_{x}=f</math> |

# If <math>f</math> is linear then <math>df_{x}=f</math> |

||

# <math>d(f\circ g)_{x}=df_{g(x)}\ |

# <math>d(f\circ g)_{x}=df_{g(x)}\cdot dg_{x}</math> |

||

# For every scalar number <math>\alpha</math> it holds <math>d(\alpha f)_{x}=\alpha df_{x}</math> |

# For every scalar number <math>\alpha</math> it holds <math>d(\alpha f)_{x}=\alpha df_{x}</math> |

||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

'''Example''' |

'''Example''' |

||

Although <math>x^2+y^2=1</math> does not |

Although <math>x^2+y^2=1</math> does not define <math>y</math> as a function of <math>x</math>, in a neighborhood of <math>(0;-1)</math> we can define <math>g(x)=-\sqrt{1-x^2}</math> so that <math>x^2+g(x)^2=1</math>. Furthermore, <math>g</math> is differentiable with differential <math>dg_{x}=\frac{x}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}</math>. This is a motivation for the following theorem. |

||

'''Notation''' |

'''Notation''' |

||

If f:X\times Y\rightarrow Z then given x\in X we will define f_{[x]}:Y\rightarrow Z by f_{[x]}(y)=f(x;y) |

If <math>f:X\times Y\rightarrow Z</math> then given <math>x\in X</math> we will define <math>f_{[x]}:Y\rightarrow Z</math> by <math>f_{[x]}(y)=f(x;y).</math> |

||

'''Definition''' |

'''Definition''' |

||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

Let <math>f:\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m</math> be a <math>C^{1}(\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m)</math> function defined on a neighborhood <math>U</math> of the point <math>(x_0;y_0)</math> and such that <math>f(x_0;y_0)=0</math> and suppose that <math>d(f_{[x]})_{y}</math> is non-singular then, the following results holds: |

Let <math>f:\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m\rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m</math> be a <math>C^{1}(\mathbb{R}^n \times \mathbb{R}^m)</math> function defined on a neighborhood <math>U</math> of the point <math>(x_0;y_0)</math> and such that <math>f(x_0;y_0)=0</math> and suppose that <math>d(f_{[x]})_{y}</math> is non-singular then, the following results holds: |

||

There is an open neighborhood of <math> |

There is an open neighborhood of <math>x_0</math>, <math>V\subset U</math>, and a ''diffable'' function <math>g:V\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^m</math> such that <math>g(x_0)=y_0</math> and for every <math>x\in V</math> <math>f(x;g(x))=0.</math>. |

||

Latest revision as of 16:23, 1 November 2007

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

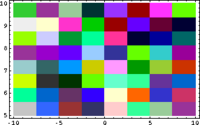

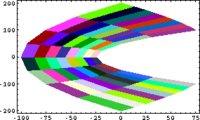

In Small Scales, Everything's Linear

|

| |

Code in Mathematica:

QuiltPlot[{f_,g_}, {x_, xmin_, xmax_, nx_}, {y_, ymin_, ymax_, ny_}] :=

Module[

{dx, dy, grid, ix, iy},

SeedRandom[1];

dx=(xmax-xmin)/nx;

dy=(ymax-ymin)/ny;

grid = Table[

{x -> xmin+ix*dx, y -> ymin+iy*dy},

{ix, 0, nx}, {iy, 0, ny}

];

grid = Map[({f, g} /. #)&, grid, {2}];

Show[

Graphics[Table[

{

RGBColor[Random[], Random[], Random[]],

Polygon[{

grid[[ix, iy]],

grid[[ix+1, iy]],

grid[[ix+1, iy+1]],

grid[[ix, iy+1]]

}]

},

{ix, nx}, {iy, ny}

]],

Frame -> True

]

]

QuiltPlot[{x, y}, {x, -10, 10, 8}, {y, 5, 10, 8}]

QuiltPlot[{x^2-y^2, 2*x*y}, {x, -10, 10, 8}, {y, 5, 10, 8}]

See also 06-240/Linear Algebra - Why We Care.

Class Notes

The notes below are by the students and for the students. Hopefully they are useful, but they come with no guarantee of any kind.

Differentiability

Let , and be two normed finite dimensional vector spaces and let be a function defined on a neighborhood of the point .

Definition:

We say that is differentiable (diffable) at if there is a linear map so that

In this case we will say that is a differential of at and will denote it by .

Theorem

If and are diffable maps then the following assertions hold:

- is unique.

- If is linear then

- For every scalar number it holds

Implicit Function Theorem

Example Although does not define as a function of , in a neighborhood of we can define so that . Furthermore, is differentiable with differential . This is a motivation for the following theorem.

Notation

If then given we will define by

Definition

will be the class of all functions defined on with continuous partial derivatives up to order

Theorem(Implicit function theorem)

Let be a function defined on a neighborhood of the point and such that and suppose that is non-singular then, the following results holds:

There is an open neighborhood of , , and a diffable function such that and for every .

![{\displaystyle f_{[x]}:Y\rightarrow Z}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9d064efbcca99f67be8a08c7c4b05c3b09db4ae3)

![{\displaystyle f_{[x]}(y)=f(x;y).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f40149c56e0edef88dc0d49abfa472172804efe)

![{\displaystyle d(f_{[x]})_{y}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/286bcb64de94afff8f12a11dbb3341620bac0600)