14-240/Classnotes for Monday September 8

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

We went over "What is this class about?" (PDF, HTML), then over "About This Class", and then over the first few properties of real numbers that we will care about.

| Dror's notes above / Students' notes below |

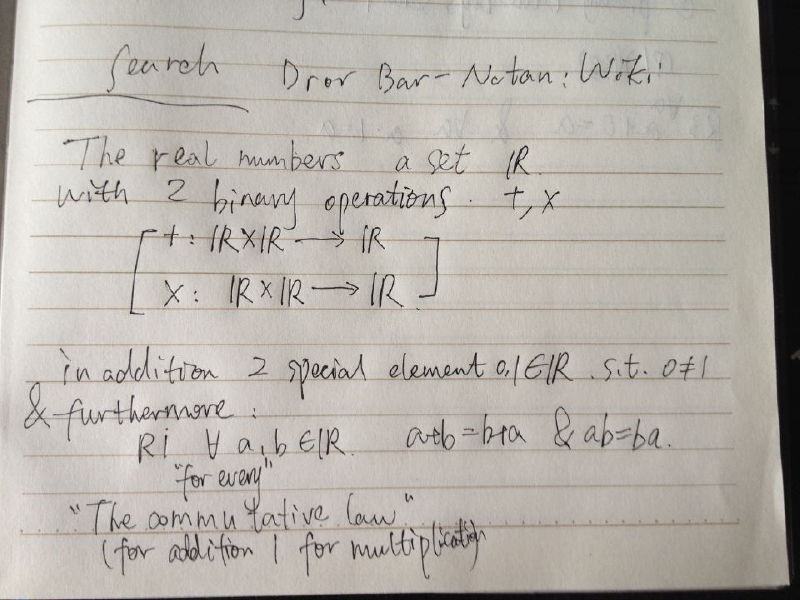

The real numbers are a set [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math] with 2 binary operations + and *, defined as follows:

[math]\displaystyle{ +: \R \times \R \rightarrow \R }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ *: \R \times \R \rightarrow \R }[/math]

in addition to 2 special elements [math]\displaystyle{ 0, 1 \in \R }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \ne 1 }[/math], with the following properties:

R1: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b \in \R }[/math], we have:

[math]\displaystyle{ a + b = b + a }[/math] (commutative law for addition) [math]\displaystyle{ ab = ba }[/math] (commutative law for multiplication)

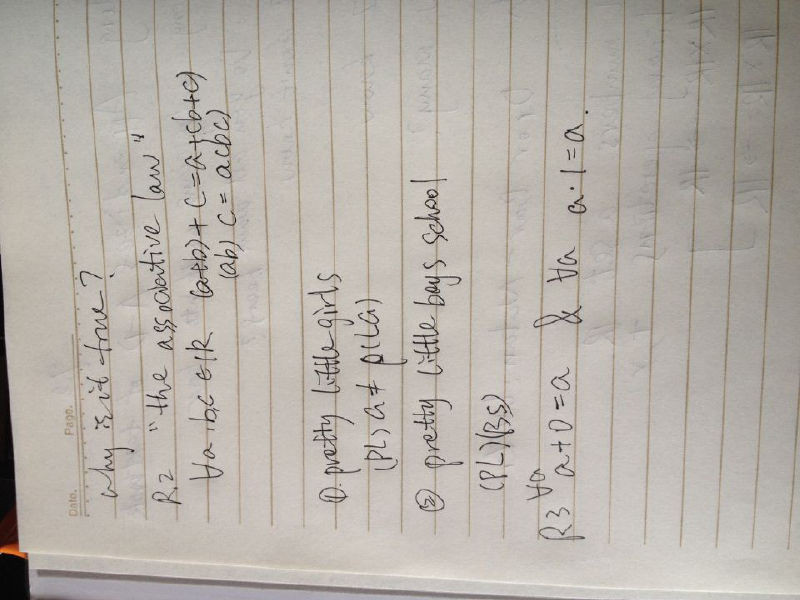

The Associative Law

R2: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b, c \in \R }[/math], we have:

[math]\displaystyle{ (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ (ab)c = a(bc) }[/math]

This is not true for a number of other sets in our lives! For example, the associative law does not hold for the English language. Consider the phrase "pretty little girls": "(pretty little) girls" does not mean the same thing as "pretty (little girls)".

[math]\displaystyle{ (PL)G \ne P(LG) }[/math]

So the associative property does not hold for the English language.

Existence of Units

R3: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a \in \R }[/math]:

[math]\displaystyle{ a + 0 = a }[/math] (additive unit) [math]\displaystyle{ a * 1 = a }[/math] (multiplicative unit)

Wednesday September 10th 2014 - Fields

The real numbers: A set |R with +,x : |R x |R -> |R & [math]\displaystyle{ 0=/=1 }[/math] are elements of |R such that

R1: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b }[/math] that are elements of |R , [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = b + a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ ab = ba }[/math]

R2: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b, c }[/math] that are elements of |R, [math]\displaystyle{ ( a + b ) + c = a + ( b + c ) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (ab)c = a(bc) }[/math]

R3: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] that is an element of |R, [math]\displaystyle{ a + 0 = a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ a * 1 = a }[/math]

R4: For every a that is an element of |R there exists b that is an element of |R such that [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = 0 }[/math] & for every a that is an element of |R and [math]\displaystyle{ a =/= 0 }[/math] there exists b that is an element |R such that [math]\displaystyle{ a * b = 1 }[/math]

R5: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b, c }[/math] that are elements of |R, [math]\displaystyle{ ( a + b ) c = ac + bc }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ ( a + b ) * ( a - b ) = a^2 - b^2 }[/math] follows from R1-R5

The following is true for the Real Numbers but does not follow from R1-R5 For every a that is an element of |R there exists an [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] that is an element of |R such that [math]\displaystyle{ a = x^2 or a + x^2 = 0 }[/math]

However we can see that it does not follow from R1-R5 because we can find a field that obeys R1-R5 yet does not follow the above rule. An example of this is the Rational Numbers |Q. In |Q take [math]\displaystyle{ a = 2 }[/math] and there does not exist [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ 2 = x^2 }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ 2 + x^2 = 0 }[/math]

The Definition Of A Field: A "Field" is a set F along with a pair of binary operations +,x : FxF -> F and along with a pair [math]\displaystyle{ 0, 1 }[/math] that are elements of F such that [math]\displaystyle{ 0 =/= 1 }[/math] and such that R1-R5 hold.

R1: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b }[/math] that are elements of F , [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = b + a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ ab = ba }[/math]

R2: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b, c }[/math] that are elements of F, [math]\displaystyle{ ( a + b ) + c = a + ( b + c ) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (ab)c = a(bc) }[/math]

R3: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] that is an element of F, [math]\displaystyle{ a + 0 = a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ a * 1 = a }[/math]

R4: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] that is an element of F there exists [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] that is an element of F such that [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = 0 }[/math] & for every [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] that is an element of F and [math]\displaystyle{ a =/= 0 }[/math] there exists [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] that is an element F such that [math]\displaystyle{ a * b = 1 }[/math]

R5: For every [math]\displaystyle{ a, b, c }[/math] that are elements of F, [math]\displaystyle{ ( a + b ) c = ac + bc }[/math]

Example

1. |R is a field (real numbers) 2. |Q is a field (rational numbers) 3. |C is a field (complex numbers) 4. F = {0, 1}

- insert table of addition and multiplication*

Proposition: F is a Field checking F5

etc...

F = {0 , 1} = F2 = Z/2

Do the same for F7

- insert table of addition and multiplication*

"Like remainders when you divide by 7" "like remainders mod 7'

Theorem (that shall remain unproved) : For every prime number P, FP = {0 , 1 , 2 , ... , p-1 } along with + & x defined as above [math]\displaystyle{ ( a , b ) -\gt a + b mod p }[/math] is a field.

Theorem: (basic properties of Fields)

Let F be a Field, and let a , b , c denote elements of F Then: 1. [math]\displaystyle{ a + b = c + b -\gt a = c }[/math] "Cancellation" still holds 2. [math]\displaystyle{ b =/= 0 , ab = cb -\gt a = c }[/math] 3. If [math]\displaystyle{ 0' }[/math] is an element of F and satisfies for every [math]\displaystyle{ a , a + 0' = a }[/math] , then [math]\displaystyle{ 0' = 0 }[/math] 4. If [math]\displaystyle{ 1' }[/math] is "like 1" then [math]\displaystyle{ 1' = 1 }[/math]

... to be continued...