0708-1300/Class notes for Tuesday, October 23

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dror's Notes

- You're all invited to my talk today at 12, "Non-Commutative Gaussian Elimination and Rubik's Cube".

- Today's office hours will go 1-2.

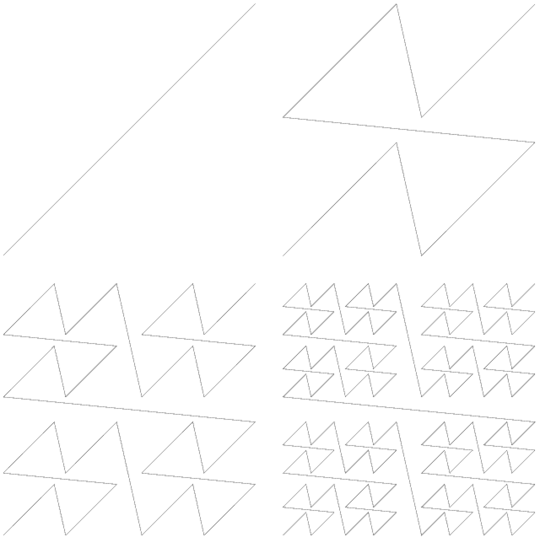

- Our handout today is a printout of a Mathematica notebook that demonstrates a "space-filling" Peano curve. Here's the notebook, and here's a PDF version. Also, here's the main picture on that notebook:

Typed Notes

The notes below are by the students and for the students. Hopefully they are useful, but they come with no guarantee of any kind.

First Hour

Diversion

It is noted that there are no smooth curves that cover the plane. However, there ARE continuous curves that cover the plane.

As an example we consider the continuous function from the unit interval to the unit square that is defined iteratively that looks like the function above.

The construction is done as follows:

draws a diagonal line from the bottom left corner to the top right corner of the unit square. For one breaks the unit interval into 7 sections. The map takes the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th sections respectively to a diagonal line in the bottom left, bottom right, top left and top right subboxes respectively where the diagonal line goes from the bottom left to the top right corner of each subbox. The 2nd, 4th and 6th "filler" sections of the unit interval simply draw the lines that map the end of one diagonal to the start of the other. The is defined iteratively. See the diagram above to see what this looks like.

We note that this is obviously continuous and we get uniform convergence to a continuous function into the unit square. As every point in the square get approached arbitrary close to a point in the image of one of the iterates of the function, compactness tells us the entire square is covered.

Definition

A general definition of "locally something" is typically that every point has a neighborhood in which this something property holds. Or perhaps a neighborhood basis where this property holds.

Hence, precisely:

1) A cover is locally finite if every point has a neighborhood V such that V intersects only finitely many 's.

2) A space is paracompact if:

a) Every open cover has a locally finite refinement

b) If a cover is locally finite then so that still covers the space but that

Note: Manifolds are paracompact

Whitney Embedding Theorem

We recall the 3 steps to prove this theorem mentioned last class. It is noted that step three will actually be broken up into two steps:

3a: For an arbitrary we can embed in

3b: We can then embed it in

Proof of Theorem

We had previously proved most of part 1, but what we still had to show was that such partitions of unity actually exist.

Reminder of Definition:

A partition of unity subordinate to is a collection of functions such that:

1) Supp

2)

Claim: If is a chart and is compact then we can find a function that is compact and supp

Proof of Claim

Because we are inside a chart, it is enough to just do this in .

For every we can find a radius r such that . By compactness we can take only finitely many such p's. Hence, cover K.

We want to put a bump function of each ball and sum them up to give us our .

Let for x<r and 0 otherwise.

Now let

Q.E.D

Theorem

On a manifold, given an open cover, you can find a partition of unity subordinate to a locally finite refinement of it.

Proof

WLOG, the cover is by charts and each one is bounded and the cover is locally finite

By paracompactness, find such that and . By the previous claim can find supp

Now consider . This is a finite sum.

By local finiteness, it is smooth and so we define

Q.E.D. for part 1 of Whitney

Second Hour

Proof of Part 2

Claim: Suppose is an embedding of a compact manifold for a large . Then an embedding .

Note: We will then backwardly induct down until it is embedded in dimension 2m+1.

Proof of Claim

We begin by noting the similarity of this with a homework problem.

Let . Such a v defines an orthogonal N-1 dimensional hyperplane. Let be the projection onto this N-1 dimensional hyperplane parallel to v.

Constructing the map , Sard's Theorem is going to show that for most such v's, this will be the embedding we are looking for.

Let us consider the v's where this does NOT work. There are two ways this will not work, either is not 1:1 or is not 1:1. Hence we will construct two function and so that the v's fail if they are in im im.

Define by

The image thus consists of points in and hence define the projection direction. Intuitively we see that this should not work because if one were to project in this direction then the two separate points and would be mapped to the same spot, thus the map would not be 1:1 and would change the topology of the resulting space. Indeed, the reverse is true,if is not 1:1 for a given projection direction then that projection direction will be in the image of

For to be an embedding we also require that (as is linear) to be 1:1 and thus will be an immersion.

This is equivalent to saying that does not "kill" anything in the image of

im im where is defined as follows:

give by, for and ,

However the domains of both 's have dimension 2m and so by Sard's Theorem, Im Im is of measure zero.

We thus choose any other and this forms a perfectly fine projection direction so the composition map is an embedding into .

By backwards induction we can repeat this procedure to get an embedding of M into

Note we can not go lower than this with these arguments since then Sard's theorem doesn't apply.

Now, to apply Sard's Theorem it was implicitly assumed that TM was itself a 2m dimensional manifold, a fact we haven't yet seen.

We can equip TM with coordinate charts in the following way.

Given a curve and a coordinate chart on the manifold we construct the function from the equivalence class of curves taking

These are of course only defined for equivalence classes in some neighborhood and it needs to be checked (easily) that this defined coordinate chart has smooth overlap functions.

Q.E.D.

Part 3 of the Proof

We start by introducing the idea of a "remoteness function"

Definition: A continuous function between topological spaces is called "proper" if the inverse image of every compact set is compact.

Consider that is smooth and proper.

So, of a compact set is compact.

Consider,

that embeds . Now this isn't quite right because is only actually a manifold for regular values t. This will be adjusted for later.

Now, for each ,

let and

The idea with these definitions is just that so that the and that ,

We now let be a smooth function such that and supp (n-3/4,n+3/4)

We now let be the embedding from part 2.

Now of course we don't always choose the numbers 2/3 and 3/4 as in the above construction, we merely choose the endpoints to be regular (possible because of Sard's Theorem) and to satisfy the appropriate properties mentioned above. Hence such exist and is a compact manifold.

Now, define and defined analogously.

We then let

This will give us the embedding we are interested in. It still remains to be shown why such a map s exists...

![{\displaystyle [\gamma ]\mapsto (\phi \circ \gamma (0),d(\phi \circ \gamma (0))\in \mathbb {R} ^{2m}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fa10e4e629b04cd52f950a5e6305a6cd5c68893)