The Existence of the Exponential Function

|

Introduction

The purpose of this paperlet is to use some homological algebra in order to prove the existence of a power series [math]\displaystyle{ e(x) }[/math] (with coefficients in [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbb Q} }[/math]) which satisfies the non-linear equation

| [Main] |

as well as the initial condition

| [Init] |

Alternative proofs of the existence of [math]\displaystyle{ e(x) }[/math] are of course available, including the explicit formula [math]\displaystyle{ e(x)=\sum_{k=0}^\infty\frac{x^k}{k!} }[/math]. Thus the value of this paperlet is not in the result it proves but rather in the allegorical story it tells: that there is a technique to solve functional equations such as [Main] using homology. There are plenty of other examples for the use of that technique, in which the equation replacing [Main] isn't as easy. Thus the exponential function seems to be the easiest illustration of a general principle and as such it is worthy of documenting.

Thus below we will pretend not to know the exponential function and/or its relationship with the differential equation [math]\displaystyle{ e'=e }[/math].

Further Examples

Before getting into our main point, which is merely to solve the equation [math]\displaystyle{ e(x+y)=e(x)e(y) }[/math], let us briefly list a number of other places in mathematics were similar "non-linear algebraic functional equations" need to be solved. The techniques we will develop to solve [Main] can be applied in all of those cases, though sometimes it is fully successful and sometimes something breaks down somewhere along the line.

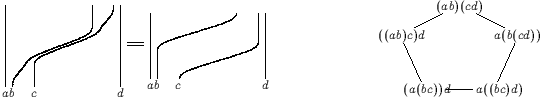

The Drinfel'd Pentagon Equation is the equation

It is an equation written in some strange non-commutative algebra [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal A}_4 }[/math], for and unknown "function" [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(a,b) }[/math] which in itself lives in some non-commutative algebra [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal A}_3 }[/math]. This equation is related to tensor categories, to quasi-Hopf algebras and (strange as it may seem) to knot theory and is commonly summarized with either of the following two pictures:

This equation is a close friend of the Drinfel'd Hexagon Equation, and you can read about both of them at

The Scheme

We aim to construct [math]\displaystyle{ e(x) }[/math] and solve [Main] inductively, degree by degree. Equation [Init] gives [math]\displaystyle{ e(x) }[/math] in degrees 0 and 1, and the given formula for [math]\displaystyle{ e(x) }[/math] indeed solves [Main] in degrees 0 and 1. So booting the induction is no problem. Now assume we've found a degree 7 polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ e_7(x) }[/math] which solves [Main] up to and including degree 7, but at this stage of the construction, it may well fail to solve [Main] in degree 8. Thus modulo degrees 9 and up, we have

| [M] |

where [math]\displaystyle{ M(x,y) }[/math] is the "mistake for [math]\displaystyle{ e_7 }[/math]", a certain homogeneous polynomial of degree 8 in the variables [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math].

Our hope is to "fix" the mistake [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] by replacing [math]\displaystyle{ e_7(x) }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ e_8(x)=e_7(x)+\epsilon(x) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon_8(x) }[/math] is a degree 8 "correction", a homogeneous polynomial of degree 8 in [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] (well, in this simple case, just a multiple of [math]\displaystyle{ x^8 }[/math]).

| *1 The terms containing no [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math]'s make a copy of the left hand side of [M]. The terms linear in [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] are [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon(x+y) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ -e_7(x)\epsilon(y) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ -\epsilon(x)e_7(y) }[/math]. Note that since the constant term of [math]\displaystyle{ e_7 }[/math] is 1 and since we only care about degree 8, the last two terms can be replaced by [math]\displaystyle{ -\epsilon(y) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ -\epsilon(x) }[/math], respectively. Finally, we don't even need to look at terms higher than linear in [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math], for these have degree 16 or more, high in the stratosphere. |

So we substitute [math]\displaystyle{ e_8(x)=e_7(x)+\epsilon(x) }[/math] into [math]\displaystyle{ e(x+y)-e(x)e(y) }[/math] (a version of [Main]), expand, and consider only the low degree terms - those below and including degree 8:*1

We define a "differential" [math]\displaystyle{ d:{\mathbb Q}[x]\to{\mathbb Q}[x,y] }[/math] by [math]\displaystyle{ (df)(x,y)=f(y)-f(x+y)+f(x) }[/math], and the above equation becomes

| *2 It is worth noting that in some a priori sense the existence of an exponential function, a solution of [math]\displaystyle{ e(x+y)=e(x)e(y) }[/math], is quite unlikely. For [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] must be an element of the relatively small space [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbb Q}[[x]] }[/math] of power series in one variable, but the equation it is required to satisfy lives in the much bigger space [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathbb Q}[[x,y]] }[/math]. Thus in some sense we have more equations than unknowns and a solution is unlikely. How fortunate we are! |

To continue with our inductive construction we need to have that [math]\displaystyle{ e_8(x+y)-e_8(x)e_8(y)=0 }[/math]. Hence the existence of the exponential function hinges upon our ability to find an [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] for which [math]\displaystyle{ M=d\epsilon }[/math]. In other words, we must show that [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is in the image of [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]. This appears hopeless unless we learn more about [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], for the domain space of [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] is much smaller than its target space and thus [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] cannot be surjective, and if [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] was in any sense "random", we simply wouldn't be able to find our correction term [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math].*2

As we shall see momentarily by "finding syzygies", [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] fit within the 0th and 1st chain groups of a rather short complex

whose first differential was already written and whose second differential is given by [math]\displaystyle{ (d^2m)(x,y,z)=m(y,z)-m(x+y,z)+m(x,y+z)-m(x,y) }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ m\in{\mathbb Q}[[x,y]] }[/math]. We shall further see that for "our" [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], we have [math]\displaystyle{ d^2M=0 }[/math]. Therefore in order to show that [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is in the image of [math]\displaystyle{ d^1 }[/math], it suffices to show that the kernel of [math]\displaystyle{ d^2 }[/math] is equal to the image of [math]\displaystyle{ d^1 }[/math], or simply that [math]\displaystyle{ H^2=0 }[/math].

Finding a Syzygy

So what kind of relations can we get for [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]? Well, it measures how close [math]\displaystyle{ e_7 }[/math] is to turning sums into products, so we can look for preservation of properties that both addition and multiplication have. For example, they're both commutative, so we should have [math]\displaystyle{ M(x,y)=M(y,x) }[/math], and indeed this is obvious from the definition. Now let's try associativity, that is, let's compute [math]\displaystyle{ e_7(x+y+z) }[/math] associating first as [math]\displaystyle{ (x+y)+z }[/math] and then as [math]\displaystyle{ x+(y+z) }[/math]. In the first way we get

[math]\displaystyle{ e_7(x+y+z)=M(x+y,z)+e_7(x+y)e_7(z)=M(x+y,z)+\left(M(x,y)+e_7(x)e_7(y)\right)e_7(z). }[/math]

In the second we get

[math]\displaystyle{ e_7(x+y+z)=M(x,y+z)+e_7(x)e_7(y+z)=M(x+y,z)+e_7(x)\left(M(y,z)+e_7(y)e_7(z)\right) }[/math].

Comparing these two we get an interesting relation for [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ M(x+y,z)+M(x,y)e_7(z) = M(x,y+z) + e_7(x)M(y,z) }[/math]. Since we'll only use [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] to find the next highest term, we can be sloppy about all but the first term of [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]. This means that in the relation we just found we can replace [math]\displaystyle{ e_7 }[/math] by its constant term, namely 1. Upon rearranging, we get the relation promised for [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ d^2M = M(y,z)-M(x+y,z)+M(x,y+z)-M(x,y) = 0 }[/math].

Computing the Homology

Now let's prove that [math]\displaystyle{ H^2=0 }[/math] for our (piece of) chain complex. That is, letting [math]\displaystyle{ M(x,y) \in \mathbb{Q}[[x,y]] }[/math] be such that [math]\displaystyle{ d^2M=0 }[/math], we'll prove that for some [math]\displaystyle{ E(x) \in \mathbb{Q}[[x]] }[/math] we have [math]\displaystyle{ d^1E = M }[/math].

Write the two power series as [math]\displaystyle{ E(x) = \sum{\frac{e_i}{i!}x^i} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ M(x,y) = \sum{\frac{m_{ij}}{i!j!}x^i y^j} }[/math], where the [math]\displaystyle{ e_i }[/math] are the unknowns we wish to solve for.

The coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ x^i y^j z^k }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ M(y,z)-M(x+y,z)+M(x,y+z)-M(x,y) }[/math] is

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\delta_{i0} m_{jk}}{j!k!} - {{i+j} \choose i} \frac{m_{i+j,k}}{(i+j)!k!} + {{j+k} \choose j} \frac{m_{i,j+k}}{i!(j+k)!} - \frac{\delta_{k0} m_{ij}}{i!j!}. }[/math]

Here, [math]\displaystyle{ \delta_{i0} }[/math] is a Kronecker delta: 1 if [math]\displaystyle{ i=0 }[/math] and 0 otherwise. Since [math]\displaystyle{ d^2 M = 0 }[/math], this coefficient should be zero. Multiplying by [math]\displaystyle{ i!j!k! }[/math] (and noting that, for example, the first term doesn't need an [math]\displaystyle{ i! }[/math] since the delta is only nonzero when [math]\displaystyle{ i=0 }[/math]) we get:

[math]\displaystyle{ \delta_{i0} m_{jk} - m_{i+j,k} + m_{i,j+k} + \delta_{k0} m_{ij}=0 }[/math].

An entirely analogous procedure tells us that the equations we must solve boil down to [math]\displaystyle{ \delta_{i0} e_j - e_{i+j} + \delta_{j0} e_i = m_{ij} }[/math].

By setting [math]\displaystyle{ i=j=0 }[/math] in this last equation we see that [math]\displaystyle{ e_0 = m_{00} }[/math]. Now let [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] be arbitrary positive integers. This solves for most of the coefficients: [math]\displaystyle{ e_{i+j} = -m_{ij} }[/math]. Any integer at least two can be written as [math]\displaystyle{ i+j }[/math], so this determines all of the [math]\displaystyle{ e_m }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ m \ge 2 }[/math]. We just need to prove that [math]\displaystyle{ e_m }[/math] is well defined, that is, that [math]\displaystyle{ m_{ij} }[/math] doesn't depend on [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] but only on their sum.

But when [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] are strictly positive, the relation for the [math]\displaystyle{ m_{ij} }[/math] reads [math]\displaystyle{ m_{i+j,k} = m_{i,j+k} }[/math], which show that we can "transfer" [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] from one index to the other, which is what we wanted.

It only remains to find [math]\displaystyle{ e_1 }[/math] but it's easy to see this is impossible: if [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ d^1E = M }[/math], then so does [math]\displaystyle{ E(x)+kx }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ e_1 }[/math] is abritrary. How do our coefficient equations tell us this?

Well, we can't find a single equation for [math]\displaystyle{ e_1 }[/math]! We've already tried taking both [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] to be zero, and also taking them both positive. We only have taking one zero and one positive left. Doing so gives two neccessary conditions for the existence of the [math]\displaystyle{ e_m }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ m_{0r} = m_{r0} = 0 }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ r\gt 0 }[/math]. So no [math]\displaystyle{ e_1 }[/math] comes up, but we're still not done. Fortunately setting one of [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] to be zero and one positive in the realtion for the [math]\displaystyle{ m_{ij} }[/math] does the trick.

References

[Bar-Natan_97] ^ D. Bar-Natan, Non-associative tangles, in Geometric topology (proceedings of the Georgia international topology conference), (W. H. Kazez, ed.), 139-183, Amer. Math. Soc. and International Press, Providence, 1997.

[Bar-Natan_Le_Thurston_03] ^ D. Bar-Natan, T. Q. T. Le and D. P. Thurston, Two applications of elementary knot theory to Lie algebras and Vassiliev invariants, Geometry and Topology 7-1 (2003) 1-31, arXiv:math.QA/0204311.

[Drinfeld_90] ^ V. G. Drinfel'd, Quasi-Hopf algebras, Leningrad Math. J. 1 (1990) 1419-1457.

[Drinfeld_91] ^ V. G. Drinfel'd, On quasitriangular Quasi-Hopf algebras and a group closely connected with [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(\bar{\mathbb Q}/{\mathbb Q}) }[/math], Leningrad Math. J. 2 (1991) 829-860.

[Le_Murakami_96] ^ T. Q. T. Le and J. Murakami, The universal Vassiliev-Kontsevich invariant for framed oriented links, Compositio Math. 102 (1996), 41-64, arXiv:hep-th/9401016.