08-401/The Fundamental Theorem: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{08-401/Navigation}} |

{{08-401/Navigation}} |

||

| ⚫ | The statement appearing here, which is a weak version of the full '''fundamental theorem of Galois theory''', is taken from Gallian's book and is meant to match our discussion in class. The proof is taken from Hungerford's book, except modified to fit our notations and conventions and simplified as per our weakened requirements. |

||

==The Fundamental Theorem of Galois Theory== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Here and everywhere below our base field <math>F</math> will be a field of characteristic 0. |

Here and everywhere below our base field <math>F</math> will be a field of characteristic 0. |

||

==Statement== |

|||

'''Theorem.''' Let <math>E</math> be a splitting field over <math>F</math>. Then there is a bijective correspondence between the set <math>\{K:E/K/F\}</math> of intermediate field extensions <math>K</math> lying between <math>F</math> and <math>E</math> and the set <math>\{H:H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\}</math> of subgroups <math>H</math> of the Galois group <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> of the original extension <math>E/F</math>: |

'''Theorem.''' Let <math>E</math> be a splitting field over <math>F</math>. Then there is a bijective correspondence between the set <math>\{K:E/K/F\}</math> of intermediate field extensions <math>K</math> lying between <math>F</math> and <math>E</math> and the set <math>\{H:H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\}</math> of subgroups <math>H</math> of the Galois group <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> of the original extension <math>E/F</math>: |

||

{{Equation*|<math>\{K:E/K/F\}\quad\leftrightarrow\quad\{H:H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\}</math>.}} |

{{Equation*|<math>\{K:E/K/F\}\quad\leftrightarrow\quad\{H:H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\}</math>.}} |

||

The bijection is given by mapping every intermediate extension <math>K</math> to the subgroup <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> of elements in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> that preserve <math>K</math>, |

The bijection is given by mapping every intermediate extension <math>K</math> to the subgroup <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> of elements in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> that preserve <math>K</math>, |

||

{{Equation*|<math>\Phi:\quad K\mapsto\operatorname{Gal}(E/K):=\{ |

{{Equation*|<math>\Phi:\quad K\mapsto\operatorname{Gal}(E/K):=\{\phi:E\to E:\phi|_K=I\}</math>,}} |

||

and reversely, by mapping every subgroup <math>H</math> of <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> to its fixed field <math>E_H</math>: |

and reversely, by mapping every subgroup <math>H</math> of <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> to its fixed field <math>E_H</math>: |

||

{{Equation*|<math>\Psi:\quad H\mapsto E_H:=\{x\in E:\forall h\in H,\ hx=x\}</math>.}} |

{{Equation*|<math>\Psi:\quad H\mapsto E_H:=\{x\in E:\forall h\in H,\ hx=x\}</math>.}} |

||

This correspondence has the following further properties: |

This correspondence has the following further properties: |

||

# It is inclusion-reversing: if <math>H_1\subset H_2</math> then <math>E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2}</math> and if <math>K_1\subset K_2</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)>\operatorname{Gal}(E/ |

# It is inclusion-reversing: if <math>H_1\subset H_2</math> then <math>E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2}</math> and if <math>K_1\subset K_2</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_2)</math>. |

||

# It is degree/index respecting: <math>[E:K]=|\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)|</math> and <math>[K:F]=[\operatorname{Gal}(E/F):\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)]</math>. |

# It is degree/index respecting: <math>[E:K]=|\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)|</math> and <math>[K:F]=[\operatorname{Gal}(E/F):\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)]</math>. |

||

# Splitting fields correspond to normal subgroups: If <math>K</math> in <math>E/K/F</math> is the splitting field of a polynomial in <math>F[x]</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> is normal in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> and <math>\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. |

# Splitting fields correspond to normal subgroups: If <math>K</math> in <math>E/K/F</math> is the splitting field of a polynomial in <math>F[x]</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> is normal in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> and <math>\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. |

||

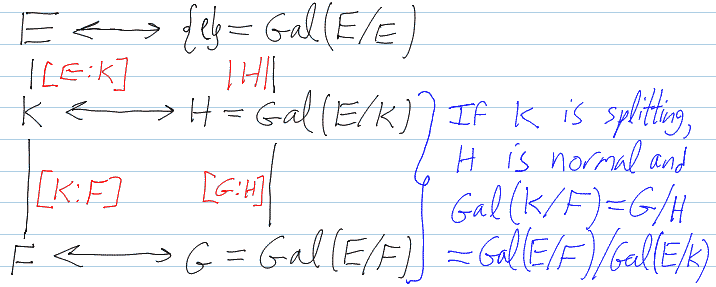

[[Image:08-401-AllInOne.png|thumb|center|716px|The Fundamental Theorem of Galois Theory, all in one.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

===Zeros of Irreducible Polynomials=== |

|||

'''Lemma 1.''' An irreducible polynomial over a field of characteristic 0 has no multiple roots. |

|||

'''Proof.''' See the proof of Theorem 20.6 on page 362 of Gallian's book. <math>\Box</math> |

|||

===Uniqueness of Splitting Fields=== |

|||

'''Lemma 2.''' Let <math>\phi:F_1\to F_2</math> be an isomorphism of fields, let <math>f_1\in F_1[x]</math> be a polynomial and let <math>f_2=\phi(f_1)</math>, and let <math>E_1</math> and <math>E_2</math> be splitting fields for <math>f_1</math> and <math>f_2</math> over <math>F_1</math> and <math>F_2</math>, respectively. Then there is an isomorphism <math>\bar\phi:E_1\to E_2</math> (generally not unique) that extends <math>\phi</math>. |

|||

'''Proof.''' See the proof of Theorem 20.4 on page 360 of Gallian's book. <math>\Box</math> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

===The Primitive Element Theorem=== |

|||

The celebrated "Primitive Element Theorem" is just a lemma for us: |

The celebrated "Primitive Element Theorem" is just a lemma for us: |

||

'''Lemma |

'''Lemma 3.''' Let <math>a</math> and <math>b</math> be algebraic elements of some extension <math>E</math> of <math>F</math>. Then there exists a single element <math>c</math> of <math>E</math> so that <math>F(a,b)=F(c)</math>. (And so by induction, every finite extension of <math>E</math> is "simple", meaning, is generated by a single element, called "a primitive element" for that extension). |

||

'''Proof.''' See the proof of Theorem 21.6 on page 375 of Gallian's book. <math>\Box</math> |

'''Proof.''' See the proof of Theorem 21.6 on page 375 of Gallian's book. <math>\Box</math> |

||

===Splitting Fields are Good at Splitting=== |

|||

'''Lemma |

'''Lemma 4.''' (Compare with Hungerford's Theorem 10.15 on page 355). If <math>E</math> is a splitting field of some polynomial <math>f</math> over <math>F</math> and some irreducible polynomial <math>p\in F[x]</math> has a root <math>v</math> in <math>E</math>, then <math>p</math> splits in <math>E</math>. |

||

'''Proof.''' Let <math>L</math> be a splitting field of <math>p</math> over <math>E</math>. We need to show that if <math>w</math> is a root of <math>p</math> in <math>L</math>, then <math>w\in E</math> (so all the roots of <math>p</math> are in <math>E</math> and hence <math>p</math> splits in <math>E</math>). Consider the two extensions |

'''Proof.''' Let <math>L</math> be a splitting field of <math>p</math> over <math>E</math>. We need to show that if <math>w</math> is a root of <math>p</math> in <math>L</math>, then <math>w\in E</math> (so all the roots of <math>p</math> are in <math>E</math> and hence <math>p</math> splits in <math>E</math>). Consider the two extensions |

||

{{Equation*|<math>E=E(v)/F(v)</math> and <math>E(w)/F(w)</math>.}} |

{{Equation*|<math>E=E(v)/F(v)</math> and <math>E(w)/F(w)</math>.}} |

||

The "smaller fields" <math>F(v)</math> and <math>F(w)</math> in these two extensions are isomorphic as they both arise by adding a root of the same irreducible polynomial (<math>p</math>) to the base field <math>F</math>. The "larger fields" <math>E=E(v)</math> and <math>E(w)</math> in these two extensions are both the splitting fields of the same polynomial (<math>f</math>) over the respective "small fields", as <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension for <math>f</math> and we can use the sub-lemma below. Thus by the uniqueness of splitting extensions, the isomorphism between <math>F(v)</math> and <math>F(w)</math> extends to an isomorphism between <math>E=E(v)</math> and <math>E(w)</math>, and in particular these two fields are isomorphic and so <math>[E:F]=[E(v):F]=[E(w):F]</math>. Since all the degrees involved are finite it follows from the last equality and from <math>[E(w):F]=[E(w):E][E:F]</math> that <math>[E(w):E]=1</math> and therefore <math>E(w)=E</math>. Therefore <math>w\in E</math>. <math>\Box</math> |

The "smaller fields" <math>F(v)</math> and <math>F(w)</math> in these two extensions are isomorphic as they both arise by adding a root of the same irreducible polynomial (<math>p</math>) to the base field <math>F</math>. The "larger fields" <math>E=E(v)</math> and <math>E(w)</math> in these two extensions are both the splitting fields of the same polynomial (<math>f</math>) over the respective "small fields", as <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension for <math>f</math> and we can use the sub-lemma below. Thus by the uniqueness of splitting extensions (lemma 2), the isomorphism between <math>F(v)</math> and <math>F(w)</math> extends to an isomorphism between <math>E=E(v)</math> and <math>E(w)</math>, and in particular these two fields are isomorphic and so <math>[E:F]=[E(v):F]=[E(w):F]</math>. Since all the degrees involved are finite it follows from the last equality and from <math>[E(w):F]=[E(w):E][E:F]</math> that <math>[E(w):E]=1</math> and therefore <math>E(w)=E</math>. Therefore <math>w\in E</math>. <math>\Box</math> |

||

'''Sub-lemma.''' If <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension of some polynomial <math>f\in F[x]</math> and <math>z</math> is an element of some larger extension <math>L</math> of <math>E</math>, then <math>E(z)/F(z)</math> is also a splitting extension of <math>f</math>. |

'''Sub-lemma.''' If <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension of some polynomial <math>f\in F[x]</math> and <math>z</math> is an element of some larger extension <math>L</math> of <math>E</math>, then <math>E(z)/F(z)</math> is also a splitting extension of <math>f</math>. |

||

| Line 46: | Line 58: | ||

and <math>E(z)</math> is obtained by adding all the roots of <math>f</math> to <math>F(z)</math>. <math>\Box</math> |

and <math>E(z)</math> is obtained by adding all the roots of <math>f</math> to <math>F(z)</math>. <math>\Box</math> |

||

==Proof of The Fundamental Theorem== |

|||

===The Bijection=== |

|||

'''Proof of <math>\Psi\circ\Phi=I</math>.''' More precisely, we need to show that if <math>K</math> is an intermediate field between <math>E</math> and <math>F</math>, then <math>E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}=K</math>. The inclusion <math>E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}\supset K</math> is easy, so we turn to prove the other inclusion. Let <math>v\in E-K</math> be an element of <math>E</math> which is not in <math>K</math>. We need to show that there is some automorphism <math>\phi\in\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> for which <math>\phi(v)\neq v</math>; if such a <math>\phi</math> exists it follows that <math>v\not\in E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}</math> and this implies the other inclusion. So let <math>p</math> be the minimal polynomial of <math>v</math> over <math>K</math>. It is not of degree 1; if it was, we'd have that <math>v\in K</math> contradicting the choice of <math>v</math>. By lemma |

'''Proof of <math>\Psi\circ\Phi=I</math>.''' More precisely, we need to show that if <math>K</math> is an intermediate field between <math>E</math> and <math>F</math>, then <math>E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}=K</math>. The inclusion <math>E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}\supset K</math> is easy, so we turn to prove the other inclusion. Let <math>v\in E-K</math> be an element of <math>E</math> which is not in <math>K</math>. We need to show that there is some automorphism <math>\phi\in\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> for which <math>\phi(v)\neq v</math>; if such a <math>\phi</math> exists it follows that <math>v\not\in E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}</math> and this implies the other inclusion. So let <math>p</math> be the minimal polynomial of <math>v</math> over <math>K</math>. It is not of degree 1; if it was, we'd have that <math>v\in K</math> contradicting the choice of <math>v</math>. By lemma 4 and using the fact that <math>E</math> is a splitting extension, we know that <math>p</math> splits in <math>E</math>, so <math>E</math> contains all the roots of <math>p</math>. Over a field of characteristic 0 irreducible polynomials cannot have multiple roots (lemma 1) and hence <math>p</math> must have at least one other root; call it <math>w</math>. Since <math>v</math> and <math>w</math> have the same minimal polynomial over <math>K</math>, we know that <math>K(v)</math> and <math>K(w)</math> are isomorphic; furthermore, there is an isomorphism <math>\phi_0:K(v)\to K(w)</math> so that <math>\phi_0|_K=I</math> yet <math>\phi_0(v)=w</math>. But <math>E</math> is a splitting field of some polynomial <math>f</math> over <math>F</math> and hence also over <math>K(v)</math> and over <math>K(w)</math>. By the uniqueness of splitting fields (lemma 2), the isomorphism <math>\phi_0</math> can be extended to an isomorphism <math>\phi:E\to E</math>; i.e., to an automorphism of <math>E</math>. but then <math>\phi|_K=\phi_0|_K=I</math> so <math>\phi\in\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>, yet <math>\phi(v)=w\neq v</math>, as required. <math>\Box</math> |

||

'''Proof of <math>\Phi\circ\Psi=I</math>.''' More precisely we need to show that if <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> is a subgroup of the Galois group of <math>E</math> over <math>F</math>, then <math>H=\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math>. The inclusion <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math> is easy. Note that <math>H</math> is finite since we've proven previously that Galois groups of finite extensions are finite and hence <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> is finite. We will prove the following sequence of inequalities: |

'''Proof of <math>\Phi\circ\Psi=I</math>.''' More precisely we need to show that if <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> is a subgroup of the Galois group of <math>E</math> over <math>F</math>, then <math>H=\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math>. The inclusion <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math> is easy. Note that <math>H</math> is finite since we've proven previously that Galois groups of finite extensions are finite and hence <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> is finite. We will prove the following sequence of inequalities: |

||

| Line 57: | Line 69: | ||

The first inequality above follows immediately from the inclusion <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math>. |

The first inequality above follows immediately from the inclusion <math>H<\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math>. |

||

By the Primitive Element Theorem (Lemma |

By the Primitive Element Theorem (Lemma 3) we know that there is some element <math>u\in E</math> so that <math>E=E_H(u)</math>. Let <math>p</math> be the minimal polynomial of <math>u</math> over <math>E_H</math>. Distinct elements of <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)</math> map <math>u</math> to distinct roots of <math>p</math>, but <math>p</math> has exactly <math>\deg p</math> roots. Hence <math>|\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)|\leq\deg p=[E:E_H]</math>, proving the second inequality above. |

||

Let <math>\sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_n</math> be an enumeration of all the elements of <math>H</math>, let <math>u_i:=\sigma_iu</math> (with <math>u</math> as above), and let <math>f</math> be the polynomial |

Let <math>\sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_n</math> be an enumeration of all the elements of <math>H</math>, let <math>u_i:=\sigma_iu</math> (with <math>u</math> as above), and let <math>f</math> be the polynomial |

||

| Line 65: | Line 77: | ||

and hence <math>f\in E_H[x]</math>. Clearly <math>f(u)=0</math>, so <math>p|f</math>, so <math>[E:E_H]=\deg p\leq \deg f=n=|H|</math>, proving the third inequality above. <math>\Box</math> |

and hence <math>f\in E_H[x]</math>. Clearly <math>f(u)=0</math>, so <math>p|f</math>, so <math>[E:E_H]=\deg p\leq \deg f=n=|H|</math>, proving the third inequality above. <math>\Box</math> |

||

===The Properties=== |

|||

'''Property 1.''' If <math>H_1\subset H_2</math> then <math>E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2}</math> and if <math>K_1\subset K_2</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)</math>. |

'''Property 1.''' If <math>H_1\subset H_2</math> then <math>E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2}</math> and if <math>K_1\subset K_2</math> then <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)</math>. |

||

| Line 80: | Line 92: | ||

'''Proof of Property 3.''' We will define a surjective (onto) group homomorphism <math>\rho:\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\to\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)</math> whose kernel is <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. This shows that <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> is normal in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> (kernels of homomorphisms are always normal) and then by the first isomorphism theorem for groups, we'll have that <math>\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. |

'''Proof of Property 3.''' We will define a surjective (onto) group homomorphism <math>\rho:\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\to\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)</math> whose kernel is <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. This shows that <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math> is normal in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> (kernels of homomorphisms are always normal) and then by the first isomorphism theorem for groups, we'll have that <math>\operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. |

||

Let <math>\sigma</math> be in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> and let <math>u</math> be an element of <math>K</math>. Let <math>p</math> be the minimal polynomial of <math>u</math> in <math>F[x]</math>. Since <math>K</math> is a splitting field, lemma |

Let <math>\sigma</math> be in <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)</math> and let <math>u</math> be an element of <math>K</math>. Let <math>p</math> be the minimal polynomial of <math>u</math> in <math>F[x]</math>. Since <math>K</math> is a splitting field, lemma 4 implies that <math>p</math> splits in <math>K[x]</math>, and hence all the other roots of <math>p</math> are also in <math>K</math>. As <math>\sigma(u)</math> is a root of <math>p</math>, it follows that <math>\sigma(u)\in K</math> and hence <math>\sigma(K)\subset K</math>. But since <math>\sigma</math> is an isomorphism, <math>[\sigma(K):F]=[K:F]</math> and hence <math>\sigma(K)=K</math>. Hence the restriction <math>\sigma|_K</math> of <math>\sigma</math> to <math>K</math> is an automorphism of <math>K</math>, so we can define <math>\rho(\sigma)=\sigma|_K</math>. |

||

Clearly, <math>\rho</math> is a group homomorphism. The kernel of <math>\rho</math> is those automorphisms of <math>E</math> whose restriction to <math>K</math> is the identity. That is, it is <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. Finally, as <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension, so is <math>E/K</math>. So every automorphism of <math>K</math> extends to an automorphism of <math>E</math> by the uniqueness statement for splitting extensions. But this means that <math>\rho</math> is onto. <math>\Box</math> |

Clearly, <math>\rho</math> is a group homomorphism. The kernel of <math>\rho</math> is those automorphisms of <math>E</math> whose restriction to <math>K</math> is the identity. That is, it is <math>\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)</math>. Finally, as <math>E/F</math> is a splitting extension, so is <math>E/K</math>. So every automorphism of <math>K</math> extends to an automorphism of <math>E</math> by the uniqueness statement for splitting extensions (lemma 2). But this means that <math>\rho</math> is onto. <math>\Box</math> |

||

Latest revision as of 15:46, 2 April 2008

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The statement appearing here, which is a weak version of the full fundamental theorem of Galois theory, is taken from Gallian's book and is meant to match our discussion in class. The proof is taken from Hungerford's book, except modified to fit our notations and conventions and simplified as per our weakened requirements.

Here and everywhere below our base field [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] will be a field of characteristic 0.

Statement

Theorem. Let [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] be a splitting field over [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math]. Then there is a bijective correspondence between the set [math]\displaystyle{ \{K:E/K/F\} }[/math] of intermediate field extensions [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] lying between [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and the set [math]\displaystyle{ \{H:H\lt \operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\} }[/math] of subgroups [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] of the Galois group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] of the original extension [math]\displaystyle{ E/F }[/math]:

The bijection is given by mapping every intermediate extension [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] to the subgroup [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math] of elements in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] that preserve [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math],

and reversely, by mapping every subgroup [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] to its fixed field [math]\displaystyle{ E_H }[/math]:

This correspondence has the following further properties:

- It is inclusion-reversing: if [math]\displaystyle{ H_1\subset H_2 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2} }[/math] and if [math]\displaystyle{ K_1\subset K_2 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)\gt \operatorname{Gal}(E/K_2) }[/math].

- It is degree/index respecting: [math]\displaystyle{ [E:K]=|\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)| }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ [K:F]=[\operatorname{Gal}(E/F):\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)] }[/math].

- Splitting fields correspond to normal subgroups: If [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E/K/F }[/math] is the splitting field of a polynomial in [math]\displaystyle{ F[x] }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math] is normal in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math].

Lemmas

The four lemmas below belong to earlier chapters but we skipped them in class (the last one was also skipped by Gallian).

Zeros of Irreducible Polynomials

Lemma 1. An irreducible polynomial over a field of characteristic 0 has no multiple roots.

Proof. See the proof of Theorem 20.6 on page 362 of Gallian's book. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Uniqueness of Splitting Fields

Lemma 2. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \phi:F_1\to F_2 }[/math] be an isomorphism of fields, let [math]\displaystyle{ f_1\in F_1[x] }[/math] be a polynomial and let [math]\displaystyle{ f_2=\phi(f_1) }[/math], and let [math]\displaystyle{ E_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ E_2 }[/math] be splitting fields for [math]\displaystyle{ f_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f_2 }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ F_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F_2 }[/math], respectively. Then there is an isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \bar\phi:E_1\to E_2 }[/math] (generally not unique) that extends [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math].

Proof. See the proof of Theorem 20.4 on page 360 of Gallian's book. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

The Primitive Element Theorem

The celebrated "Primitive Element Theorem" is just a lemma for us:

Lemma 3. Let [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] be algebraic elements of some extension [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math]. Then there exists a single element [math]\displaystyle{ c }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] so that [math]\displaystyle{ F(a,b)=F(c) }[/math]. (And so by induction, every finite extension of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] is "simple", meaning, is generated by a single element, called "a primitive element" for that extension).

Proof. See the proof of Theorem 21.6 on page 375 of Gallian's book. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Splitting Fields are Good at Splitting

Lemma 4. (Compare with Hungerford's Theorem 10.15 on page 355). If [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] is a splitting field of some polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] and some irreducible polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ p\in F[x] }[/math] has a root [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] splits in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math].

Proof. Let [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] be a splitting field of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. We need to show that if [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is a root of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ w\in E }[/math] (so all the roots of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] are in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and hence [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] splits in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]). Consider the two extensions

The "smaller fields" [math]\displaystyle{ F(v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F(w) }[/math] in these two extensions are isomorphic as they both arise by adding a root of the same irreducible polynomial ([math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]) to the base field [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math]. The "larger fields" [math]\displaystyle{ E=E(v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ E(w) }[/math] in these two extensions are both the splitting fields of the same polynomial ([math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]) over the respective "small fields", as [math]\displaystyle{ E/F }[/math] is a splitting extension for [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] and we can use the sub-lemma below. Thus by the uniqueness of splitting extensions (lemma 2), the isomorphism between [math]\displaystyle{ F(v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F(w) }[/math] extends to an isomorphism between [math]\displaystyle{ E=E(v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ E(w) }[/math], and in particular these two fields are isomorphic and so [math]\displaystyle{ [E:F]=[E(v):F]=[E(w):F] }[/math]. Since all the degrees involved are finite it follows from the last equality and from [math]\displaystyle{ [E(w):F]=[E(w):E][E:F] }[/math] that [math]\displaystyle{ [E(w):E]=1 }[/math] and therefore [math]\displaystyle{ E(w)=E }[/math]. Therefore [math]\displaystyle{ w\in E }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Sub-lemma. If [math]\displaystyle{ E/F }[/math] is a splitting extension of some polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ f\in F[x] }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] is an element of some larger extension [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ E(z)/F(z) }[/math] is also a splitting extension of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math].

Proof. Let [math]\displaystyle{ u_1,\ldots,u_n }[/math] be all the roots of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. Then they remain roots of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E(z) }[/math], and since [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] completely splits already in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], these are all the roots of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E(z) }[/math]. So

and [math]\displaystyle{ E(z) }[/math] is obtained by adding all the roots of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ F(z) }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Proof of The Fundamental Theorem

The Bijection

Proof of [math]\displaystyle{ \Psi\circ\Phi=I }[/math]. More precisely, we need to show that if [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is an intermediate field between [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}=K }[/math]. The inclusion [math]\displaystyle{ E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)}\supset K }[/math] is easy, so we turn to prove the other inclusion. Let [math]\displaystyle{ v\in E-K }[/math] be an element of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] which is not in [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math]. We need to show that there is some automorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \phi\in\operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math] for which [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(v)\neq v }[/math]; if such a [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] exists it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ v\not\in E_{\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)} }[/math] and this implies the other inclusion. So let [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] be the minimal polynomial of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math]. It is not of degree 1; if it was, we'd have that [math]\displaystyle{ v\in K }[/math] contradicting the choice of [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math]. By lemma 4 and using the fact that [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] is a splitting extension, we know that [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] splits in [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] contains all the roots of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. Over a field of characteristic 0 irreducible polynomials cannot have multiple roots (lemma 1) and hence [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] must have at least one other root; call it [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math]. Since [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] have the same minimal polynomial over [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math], we know that [math]\displaystyle{ K(v) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ K(w) }[/math] are isomorphic; furthermore, there is an isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_0:K(v)\to K(w) }[/math] so that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_0|_K=I }[/math] yet [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_0(v)=w }[/math]. But [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] is a splitting field of some polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] and hence also over [math]\displaystyle{ K(v) }[/math] and over [math]\displaystyle{ K(w) }[/math]. By the uniqueness of splitting fields (lemma 2), the isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_0 }[/math] can be extended to an isomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \phi:E\to E }[/math]; i.e., to an automorphism of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. but then [math]\displaystyle{ \phi|_K=\phi_0|_K=I }[/math] so [math]\displaystyle{ \phi\in\operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math], yet [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(v)=w\neq v }[/math], as required. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Proof of [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\circ\Psi=I }[/math]. More precisely we need to show that if [math]\displaystyle{ H\lt \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] is a subgroup of the Galois group of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ H=\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math]. The inclusion [math]\displaystyle{ H\lt \operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math] is easy. Note that [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] is finite since we've proven previously that Galois groups of finite extensions are finite and hence [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] is finite. We will prove the following sequence of inequalities:

This sequence and the finiteness of [math]\displaystyle{ |H| }[/math] imply that these quantities are all equal and since [math]\displaystyle{ H\lt \operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math] it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ H=\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math] as required.

The first inequality above follows immediately from the inclusion [math]\displaystyle{ H\lt \operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math].

By the Primitive Element Theorem (Lemma 3) we know that there is some element [math]\displaystyle{ u\in E }[/math] so that [math]\displaystyle{ E=E_H(u) }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] be the minimal polynomial of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] over [math]\displaystyle{ E_H }[/math]. Distinct elements of [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H) }[/math] map [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to distinct roots of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], but [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] has exactly [math]\displaystyle{ \deg p }[/math] roots. Hence [math]\displaystyle{ |\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)|\leq\deg p=[E:E_H] }[/math], proving the second inequality above.

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_n }[/math] be an enumeration of all the elements of [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ u_i:=\sigma_iu }[/math] (with [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] as above), and let [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] be the polynomial

Clearly, [math]\displaystyle{ f\in E[x] }[/math]. Furthermore, if [math]\displaystyle{ \tau\in H }[/math], then left multiplication by [math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math] permutes the [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_i }[/math]'s (this is always true in groups), and hence the sequence [math]\displaystyle{ (\tau u_i=\tau\sigma u_i)_{i=1}^n }[/math] is a permutation of the sequence [math]\displaystyle{ (u_i)_{i=1}^n }[/math], hence

and hence [math]\displaystyle{ f\in E_H[x] }[/math]. Clearly [math]\displaystyle{ f(u)=0 }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ p|f }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ [E:E_H]=\deg p\leq \deg f=n=|H| }[/math], proving the third inequality above. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

The Properties

Property 1. If [math]\displaystyle{ H_1\subset H_2 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ E_{H_1}\supset E_{H_2} }[/math] and if [math]\displaystyle{ K_1\subset K_2 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1)\gt \operatorname{Gal}(E/K_1) }[/math].

Proof of Property 1. Easy. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]

Property 2. [math]\displaystyle{ [E:K]=|\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)| }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ [K:F]=[\operatorname{Gal}(E/F):\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)] }[/math].

Proof of Property 2. If [math]\displaystyle{ K=E_H }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ |\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)|=|\operatorname{Gal}(E/E_H)|=[E:E_H]=[E:K] }[/math] as was shown within the proof of [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi\circ\Psi=I }[/math]. But every [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ E_H }[/math] for some [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math], so [math]\displaystyle{ |\operatorname{Gal}(E/K)|=[E:K] }[/math] for every [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] between [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math]. The second equality follows from the first and from the multiplicativity of the degree/order/index in towers of extensions and in towers of groups:

Property 3. If [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ E/K/F }[/math] is the splitting field of a polynomial in [math]\displaystyle{ F[x] }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math] is normal in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math].

Proof of Property 3. We will define a surjective (onto) group homomorphism [math]\displaystyle{ \rho:\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)\to\operatorname{Gal}(K/F) }[/math] whose kernel is [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math]. This shows that [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math] is normal in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] (kernels of homomorphisms are always normal) and then by the first isomorphism theorem for groups, we'll have that [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(K/F)\cong\operatorname{Gal}(E/F)/\operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] be in [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/F) }[/math] and let [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] be an element of [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] be the minimal polynomial of [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ F[x] }[/math]. Since [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is a splitting field, lemma 4 implies that [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] splits in [math]\displaystyle{ K[x] }[/math], and hence all the other roots of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] are also in [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math]. As [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(u) }[/math] is a root of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], it follows that [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(u)\in K }[/math] and hence [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(K)\subset K }[/math]. But since [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is an isomorphism, [math]\displaystyle{ [\sigma(K):F]=[K:F] }[/math] and hence [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(K)=K }[/math]. Hence the restriction [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma|_K }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is an automorphism of [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math], so we can define [math]\displaystyle{ \rho(\sigma)=\sigma|_K }[/math].

Clearly, [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is a group homomorphism. The kernel of [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is those automorphisms of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] whose restriction to [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is the identity. That is, it is [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Gal}(E/K) }[/math]. Finally, as [math]\displaystyle{ E/F }[/math] is a splitting extension, so is [math]\displaystyle{ E/K }[/math]. So every automorphism of [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] extends to an automorphism of [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] by the uniqueness statement for splitting extensions (lemma 2). But this means that [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is onto. [math]\displaystyle{ \Box }[/math]